Mia enjoying the neighborhood playground

Mia Gets a Second Chance After Liver Transplant

From the moment she was born, Mia has been daddy’s girl. Her frequent smiles make him laugh. Her nighttime cuddles on his chest, nuzzling her head under his chin, warms his heart and reminds him of the first time he held her in his arms.

“She was born the day of the Grammy Awards,” says Mia’s father, Leandro, a music producer. “There I was, sitting and holding my newborn baby, watching the Grammys on my phone and I won a Grammy that same day. I was ecstatic.”

Leandro and his wife, Sara, orchestrated a harmonious routine caring for little Mia and her older brother, Liam, 2. Because Leandro tended to work late at night, Sara would go to bed early and get up early, and Leandro would take care of Mia’s late-night feedings and diaper changes. Everything was going well except that Mia’s eyes were yellow. The doctors chalked it up to a common condition known as breast milk jaundice, which can occur in newborns due to higher levels of bilirubin, the yellowish pigment produced during the normal breakdown of red blood cells, which is then processed by the liver. Generally, the condition is not harmful and goes away within a few weeks.

But in Mia’s case, the yellowing of her eyes persisted. Following a blood draw at her two-month checkup, Mia’s pediatrician instructed Sara and Leandro to take her to the hospital for more tests.

“We celebrated our five-year wedding anniversary by taking the kids for a hike in Malibu,” Leandro says. “Literally the next day, Mia’s bloodwork results came in and we were at the hospital.”

A devastating diagnosis

After additional tests and scans, doctors at a local hospital diagnosed Mia with biliary atresia, a liver disease that causes inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts inside and outside of the liver. In healthy babies, bile ducts carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and eventually to the small intestine. Bile includes chemicals that the body is trying to get rid of. When the bile ducts are blocked, toxic chemicals collect in the liver. This is called cholestasis. This can lead to cirrhosis (severe scarring) by 6 to 12 months of age. Doctors recommended that Mia receive a Kasai procedure, which would replace her damaged bile ducts and gallbladder with a piece of her own small intestine.

Following the Kasai procedure, Mia developed ascites, a buildup of fluid in the abdomen that is common in patients with a liver disorder. Doctors informed Leandro and Sara that Mia would likely need a liver transplant—which was outside their scope of treatment—and referred them to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Trusting the experts

“We called a few people, and they said ‘CHLA is the best place you can go,’” Leandro says. “Looking back, we are so grateful we did.”

Established more than 25 years ago, the Liver Transplant Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is one of the largest in the country and has performed more than 500 pediatric liver transplants.

“Mia had progressed to end-stage liver disease,” says Kambiz Etesami, MD, Director of Abdominal Transplantation, and Surgical Director, Liver and Intestinal Transplant at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, noting that Mia was malnourished due to an inability to digest and absorb nutrients. She received intravenous nutrition, but because her liver was so badly damaged, fluid continued to build up.

“Liver transplantation is a specialized field, and pediatric liver transplant is even more specialized,” says Dr. Etesami. “It can be very challenging to find an organ from another infant. You might be waiting a long time, and often these children don’t have much time.”

On June 4, 2024, Mia was placed on the pediatric liver transplant list. As her condition worsened, the ascites impacted her breathing and required specialists in Interventional Radiology to drain the fluid from her abdomen every few days. Despite her critical condition, the tests used to assess a patient’s priority on the transplant list did not reflect Mia’s true level of need. The scoring system that prioritizes patients for liver transplants is far from perfect, particularly for infants and young children, often underestimating the severity of their illness. This was precisely the case for Mia.

“Part of my role is advocating for patients,” explains George Yanni, MD, Director, Transplant Hepatology Fellowship Program, who wrote multiple letters to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) about Mia’s case. “I try to reassure them as much as I can that I will fight for her—and that’s what we did.”

Less than three weeks after she was added to the transplant list, a liver donor was located for Mia.

A second chance at life

On the day of her transplant, Mia’s belly measured nearly 60 centimeters in girth and more than one liter of fluid was drained from her abdomen. The 11-hour transplant surgery was complex for the team because of Mia’s size—she weighed less than 9 lbs.

“Transplants for a small baby are technically challenging, especially when we are making the connections between the new liver and the body,” Dr. Etesami says. “The blood vessels are very small, often 2 or 3 millimeters, so we do this type of surgery under what we call a surgical loop—a microscope.”

“We are experts at transplants, but it’s never a one-man show,” adds Dr. Yanni. “It’s a whole team effort, from the nurse coordinator to the transplant hepatologists, the attending staff on service, the social workers, the nurses, the nutritionists, the surgeons.”

The family was overcome with gratitude to Mia’s entire care team, and to the organ donor’s family.

“We wrote a letter to the donor family to let them know that during their hardest time, they saved our 4-month-old daughter’s life,” Sara says, tearing up as she reflects on the magnitude of organ donation. “A lot of people have that red dot on their driver’s license, but until you go through it, and you are waiting for an organ on the other end, you have no idea what those selfless acts of people donating loved ones’ organs are doing for the family on the other side, waiting.”

Three weeks after her transplant, Mia was discharged. Because of her fragile immune system, she and the family isolated at home for the first three months. Sara, a former schoolteacher, focused on helping Mia reach some critical infant milestones like holding her head up, rolling over, and sitting up on her own.

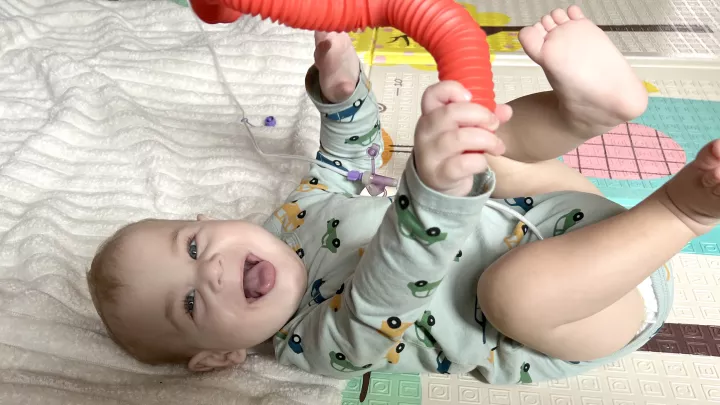

Now 8 months old, Mia enjoys daily activities like mat time, reading, playing with her toys, and trying to do whatever her big brother is doing. She’s also “mostly” sleeping through the night, Leandro says, and she’s eating solid foods. Another milestone for Mia? She’s found her voice—and she isn’t afraid to use it.

“She squeals and she sounds like a pterodactyl!” Leandro says of his daughter, who he affectionately calls “my spicy chicken nugget. She has FOMO (fear of missing out) and does not like sitting down. If she’s sitting in her chair and she wants to get up, she’ll squeal and start throwing her toys at me!”

As for Mia’s prognosis, Dr. Etesami says it’s “very good,” noting that her surgery and her early weeks of recovery went smoothly. “Most kids can have many decades of essentially ‘normal’ lives with a transplanted liver.”

Mia currently takes seven different medications, has weekly blood draws, and sees her doctor once a month. Because of their experience, Sara and Leandro have become mini medical experts and hope to be a resource for other families facing a similar health challenge.

“We understand there will be parents in the same situation we were in before we got to the brighter side of things,” Leandro says. “I remember how we felt during that time, and how comforting it was to know people out there went through the same thing and had positive experiences. CHLA has done so much for us.”

So far, 2024 has been a whirlwind of surprises for the family, who are grateful for every moment they have together.

“CHLA gave our whole family a second chance,” Sara says. “We couldn’t be more thankful to every person we met along the way that helped us. I still call the nurses with questions, and they are always warm and helpful. They never make me feel like I’m bothering them.”

At CHLA, patients and their families are never far from their care team’s minds or hearts.

“Mia is very close to my heart,” Dr. Yanni says. “For parents, their kids are so precious. We know this and that is why we work so hard.”