Teen Receives Historic Heart-Liver Transplant

Knuckle bumps are good for casual goodbyes; hugs and kisses for airport partings. But after exchanging both with his mother, Melissa, Mark found that they weren’t enough to seal a preop farewell. Certainly not one of this magnitude.

From the operating room before the day-long dual surgeries that would make him the first heart-liver transplant recipient at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, he asked one of the transplant team members to get a message to his mom.

Melissa heard her phone chime when it arrived: “Mark wanted me to tell you that he loves you.”

Complications from the Fontan

She was 16 when she had Mark, and only seconds after he was born he abruptly stopped crying, indicating something wasn’t right. The doctor came in to explain what it was.

“I was very confused,” Melissa says. “Was there something I did wrong? I remember him drawing out a normal heart for me, and drawing out Mark's heart.”

The issue was hypoplastic right heart syndrome, a congenital disorder that leaves the right chamber of the heart underdeveloped and unable to pump blood. Doctors have to perform a trio of precisely sequenced surgeries in the baby’s first few years of life to reconfigure the heart so the one good ventricle can take over for the incapacitated side. Over time, the extra burden on the working ventricle can’t be sustained; usually a heart transplant is unavoidable.

Mark tolerated the first two surgeries—one at 5 days old, the other at 6 months—but had complications from the third one, called the Fontan. During the procedure the vein that carries blood back from the body, the inferior vena cava, is disconnected from the heart and attached to the pulmonary artery so blood flows straight to the lungs, sidestepping the nonfunctioning right ventricle altogether.

The makeshift “Fontan circulation” produces new threats, though. Elevated blood pressure within the veins can cause blood flow to jam up in the liver, inflicting damage.

“The liver and the heart are intimately involved with each other,” CHLA heart surgeon Cynthia Herrington, MD, says. “When the pressures in the Fontan circuit go up, it’s not uncommon for us to see liver failure.”

After Mark underwent the procedure in December 2009 at age 3, his liver began to show abnormalities, triggering a particularly malevolent disorder called protein-losing enteropathy, or PLE. Body fluids begin leaking into the intestines, causing diarrhea, the loss of proteins and nutrients—and extreme fatigue.

“I would wake him up in the morning for school,” Melissa says. “He would get ready for his day, and then by the time we got to the stoplight, he would be asleep again.”

Over time, his struggles with PLE accelerated Mark’s need for a heart transplant, as his body risked becoming too malnourished to support one. In the summer of 2017, he was listed for a heart transplant. The wait for a donor would reach three years, prompting Mark’s cardiologist, Jondavid Menteer, MD, to push for him to be admitted to the hospital. With Mark as an inpatient, doctors could more forcefully treat his symptoms—and it would also raise his standing on the waiting list.

“Having him in the hospital,” Dr. Menteer says, “actively giving him IV nutrition and other medications, allowed us to get his urgency up.”

In October 2020, Mark, now 14, was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles with the hope of fortifying his system for a transplant—or transplants, Dr. Menteer says. “That was about the same time we also decided his liver was doomed to fail.”

Coming to consensus

Scans showed Mark’s liver was overrun with tumors. They appeared benign, but were growing and could eventually turn cancerous. It was becoming clear that he needed both his heart and liver replaced, taking him into territory only 16 other kids had gone previously—none at CHLA.

Prior to Mark’s case, if a Children’s Hospital patient had advanced heart and liver disease, the heart transplant would be done and perhaps help to heal the liver, if it was still salvageable.

“For years that's what we did,” says Dr. Herrington, Surgical Director of the hospital’s Heart Transplant Program. “We’d do the heart transplant and hope we were in time to get the liver to reverse its pathology.”

But patients whose livers were too far gone were excluded from a transplant because they were judged to be too weak to survive it. That inability to provide treatment tore at Dr. Herrington.

“It was incredibly disheartening,” she says, “to go to families and say, ‘We're not going to be able to do it. I don't have anything to offer.’”

Mark’s liver was sick, but not too sick. However, that status would tip before much longer, and leaving the liver alone would sentence Mark and his mother to regularly having the tumors monitored and biopsied for cancer.

“The nodules were getting larger and the liver was filled with them,” Dr. Herrington says. “We either had to commit to doing the liver as well, or not do the heart transplant. We have so many Fontan patients with liver impairment, it was time for us to commit to adding this to our surgical repertoire.”

As they discussed the prospect of a heart-liver transplant, she and Yuri Genyk, MD, Division Chief of Abdominal Organ Transplantation, agreed it was the most sensible, safest path forward. “We were both in the same space with it,” she says. “We were finishing each other's sentences.”

Dr. Menteer was less sure. He sought to be persuaded, quizzing the members of the liver transplant team. “I was asking every last question,” he says. “What happens if we don't do this? What's our likelihood of success if we just replaced his heart? What are the complications going to be? I needed to be shown that the risks were justified.”

The abject state of Mark’s liver, the looming cancer threat, and the greater likelihood of the heart transplant’s success if it was joined by a new liver eventually swayed him.

“Ultimately I was convinced by everybody's expertise that this was a patient who needed a liver transplant.”

Plans A, B, C and C-apostrophe

It was Dr. Menteer who found in a research database that there were only 16 previous pediatric heart-liver transplants in the U.S. That left the doctors with few colleagues to consult.

“It's not like I could call somebody and say, ‘Hey, what's your experience with the last 10 heart-livers you've done in a pediatric population?’” Dr. Herrington says.

Instead, she and Dr. Genyk leaned on each other. “You cannot rehearse the operation,” Dr. Genyk says. “But you can plan.”

They proceeded to talk it out, frequently and in rigorous detail.

“There was a lot of preoperative strategy and conversation,” Dr. Herrington says. “We had the A plan, we had the B plan, we had the C plan. And if this happened and we had to do, like, C-apostrophe, what would that look like? We had scenarios planned out for pretty much anything that could have been thrown at us.”

They were not alone in having to coordinate their steps. Eleven hospital teams would participate in the two operations. The checkerboard of faces in the Webex meetings stretched to more than 100 squares, Dr. Menteer says. “We had every detail of Mark’s pre-transplant course, transplant donor selection course, transplant operative course and post-transplant critical care course planned out.”

Plus, the two surgeons knew they were on comfortable ground.

“I was going to do a heart transplant, which I've spent 22 years doing,” Dr. Herrington says. “Yuri did say in the beginning, ‘You know, Cindy, you're going to do what you do all the time, and I'm going to do what I do all the time. I think it's going to be fine.’”

‘An incredible thing’

In early 2021, Melissa received a call from one of the hospital’s transplant coordinators: A donor had been found.

“I just got quiet,” Melissa says. “She said, ‘Melissa, are you still there?’ I said, ‘Yes, I'm still here, but I'm waiting for the rest of the information you're going to tell me.’”

She braced for the disclaimer. “There’s always a 'but' or an ‘and' or 'we have to do more tests,' so I was waiting for that part.”

She was assured there was no other part. The surgery would be the next morning, pending the review and approval of the donated heart and liver, which came hours later.

Dr. Herrington went in first, at 5:30 a.m., and by noon she had placed Mark’s new heart and turned the operating room over to Dr. Genyk, who over the next several hours transplanted the liver, noting it went smoothly thanks to the excellent function of the donated heart. “That made the operation relatively straightforward for us.”

At 10:30 p.m., after Dr. Herrington returned to the OR to close up Mark’s chest, the exhaustive surgery was done. “Everything went really well,” she says. “There were no surprises.”

After handing Mark over to the ICU staff, Dr. Herrington went home and fell easily to sleep, but was awakened at 3 a.m., startled by something she couldn’t quite sort out.

“I woke up in tears,” she says, "wondering, why am I crying? What's happening?”

The enormity of what she and her colleagues had achieved overcame her. “It was like, oh my god, what have we done? We have done an incredible thing.”

When she got to her office the next day, she wrote a thank-you letter that addressed every individual who participated on surgery day. “I had a page and a half of names,” she says.

She had had her moment and was there a few days afterward when Dr. Genyk, who had been keeping to his routines, had his.

“Yuri came to my office. He sat down and closed the door. He said, ‘That was so stressful.’ I said, ‘Yeah, see? You’re having your moment. It was a thing, right?’ He said, ‘Yeah, it was a thing.’”

It will stay a thing, assuming its place as a landmark in the history of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles—the first-ever heart-liver transplant. It doesn’t figure to be the last.

“We have a large Fontan population at CHLA,” Dr. Herrington says. “It makes me feel really good that I now have something to offer them that I know our team is capable of delivering.”

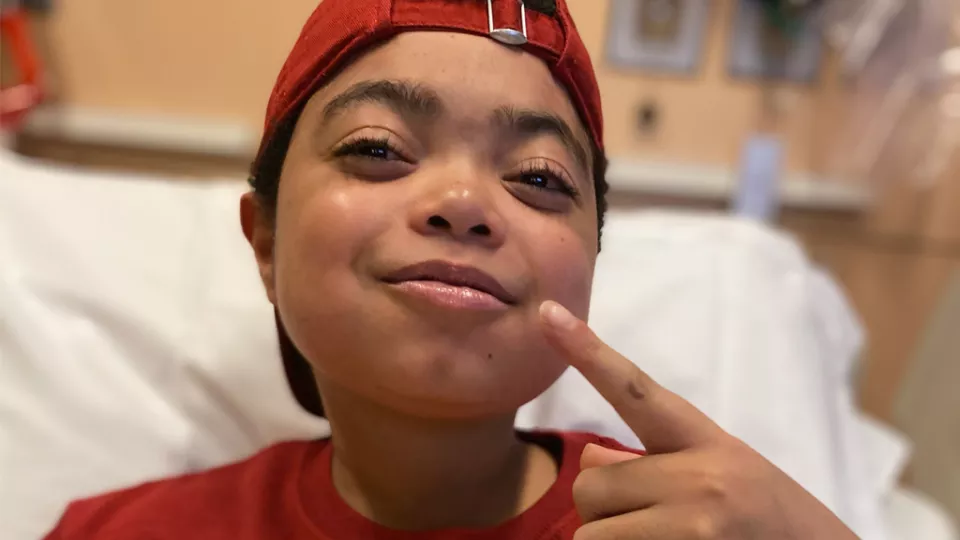

Mark continues to heal, making regular clinic visits to Dr. Menteer. He’s taking immunosuppressant medicines to keep his immune system from rejecting the new organs. A biopsy of his heart showed no signs of mutiny.

“He looks fantastic,” Dr. Menteer says. “He's got more energy, he's eating like crazy. He doesn't have any PLE symptoms. I imagine that six months to a year from now, it will be night-and-day difference. He'll be well-nourished, more fit and feeling better in every aspect.”

There are a few food restrictions Mark has to follow, so he’s trying some workarounds. Raw sushi is out; instead he has baked salmon rolls. In place of pomegranates—too acidic—he eats grapes. Steak is OK, but he can’t have his preferred medium-rare.

“Well-done is good too,” he says. “I’ve gotten used to it.”

He’s learning to live with substitutes, including the two that will give him life for decades more.