A Closer Look: Why Is Research Essential at a Children’s Hospital?

Medicine is an ever-changing field. Treatments evolve from basic and translational research, advance to clinical trials and if successful, are introduced into the clinic. But it doesn’t stop there. It can’t. There’s always the potential to get diagnoses sooner, to make treatments more effective and to turn what we learn into a more personalized approach for individual patients.

The ambitions of pediatric researchers are global in scale: Beyond patients at their own hospital, they look to shape national and international standards for pediatric care. These goals are best achieved through the very special relationship between research and clinical care. True change comes from an environment that fosters thought and innovation as much as it values treating disease. It comes from a culture of constantly questioning—always searching for better ways to do things.

The following stories showcase researchers who are changing the landscape of pediatric medicine and answering the question: Why is research essential at a children’s hospital?

Because discovery can be fast-tracked to the kids who need it.

The next big medical breakthrough might be taking place right this very minute. But here’s the thing: It may not look anything like a medical breakthrough. That’s because discovery starts with basic research that investigates the mechanisms of pediatric diseases. It can take years before these discoveries lead to therapeutics and more years before these advances make their way into the clinic. That’s why research at a children’s hospital is so crucial. Here, investigators are steeped in a research environment that’s directly informed by patient need. And in this environment, discoveries can benefit patients more quickly.

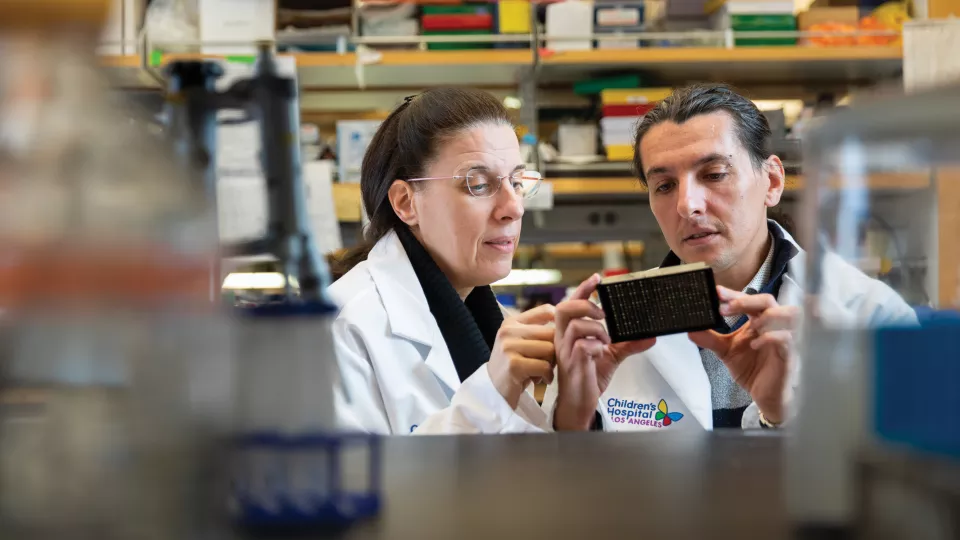

Meet Laura Perin, PhD, and Stefano Da Sacco, PhD, two scientists in the GOFARR Laboratory for Organ Regenerative Research and Cell Therapeutics in Urology. Drs. Perin and Da Sacco study diseases of the kidney, the body’s main filter for toxins and wastes. “Learning exactly how renal filtration occurs has been difficult,” says Dr. Perin, “because we don’t have a good laboratory model.” This is no small point. Accurate modeling of how human cells work in the body is critical to studying any disease.

Recently, Drs. Perin and Da Sacco developed a revolutionary model in which healthy human kidney cells grow into a filtration barrier, just as they do in the human body. This tool—which fits in the palm of your hand—is much more powerful than the sum of its parts. The device mimics the filtering action of the kidneys. The model has many potential uses, like testing the safety of new medications prior to clinical trials.

An individual patient’s disease progression can even be monitored by running serum samples through the device, allowing researchers to see how certain factors circulating in the blood affect kidney function. This, in turn, can set the stage for more personalized care.

“Doing this research at a children’s hospital is critical,” says Dr. Da Sacco. There are many reasons for this, including access to healthy and diseased tissue samples for research. But there’s something about being in a pediatric hospital that doesn’t translate to any other lab. “We’re in this environment where people are working on so many different levels to help these kids live longer, healthier lives,” he says. “What better motivation to work hard could there be?”

Because existing treatments can be made better when the people who treat patients also do research.

Leukemia—specifically acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL—has one of the highest survival rates of any cancer. Up to 90% of children are in remission at their five-year follow-up appointment. So why do doctors like Etan Orgel, MD, MS, choose to work on improving therapies for cancers like this? For one thing, 90% isn’t 100%. “Even though this is the best success rate we’ve ever had in treating leukemia, not every child beats the disease,” says Dr. Orgel. If existing chemotherapies could be made more effective, more patients could go into remission.

Basic and translational research shows that the body’s fat cells can actually get in the way of treatments by shielding cancer cells and making chemotherapy less effective. Based on this knowledge, Dr. Orgel and his team initiated the IDEAL study (Improving Diet and Exercise in ALL). Patients reduce their calorie intake and participate in light exercise during the first phase of chemotherapy. This change alone reduced the risk of detectible cancer cells—known as minimal residual disease—at the end of the first phase of chemotherapy.

What’s more, this reduced risk involves no additional medications or treatments. “These kids are already going through so much during chemotherapy,” says Dr. Orgel. “The goal is to improve their chances without adding in more pills, more side effects and more stress on the body.”

Based on the success of the first phase of the IDEAL study, Dr. Orgel and his team have initiated IDEAL 2, which is currently enrolling patients across the United States.

When asked why it’s important to conduct research at a children’s hospital, he says that there would be no other way. “Children aren’t just small adults, and we can’t treat their cancers the same way,” he says. Pediatric cancers are often very different from adult cancers, and treatments required are different, too. This necessitates special research. “Unfortunately, because pediatric cancer is relatively rare, it is underfunded and under-resourced,” says Dr. Orgel. “Children’s hospitals play a crucial role in bridging this gap. The goal is to improve their chances without adding in more pills, more side effects and more stress on the body.”

Because sometimes, the clinic is where the most pressing research questions—and solutions—are born.

Jesse Berry, MD, didn’t set out to do research. She went to medical school so she could help children in need. After all, she says doctors were quite impactful in her own upbringing. But help comes in many forms, and in Dr. Berry’s case, help turned out to be discovering a better way to diagnose retinoblastoma. This cancer—which develops at the back of the eye and can lead to blindness—has always been a problem to diagnose.

“You can’t biopsy it like other cancer,” she explains. “Performing the biopsy can help the cancer spread.” Instead, doctors must rely on imaging to diagnose the disease. When it comes to retinoblastoma, arriving at a definitive diagnosis sooner could mean saving a child’s vision.

Enter Dr. Berry, the A. Linn Murphree, MD, Chair in Ocular Oncology, whose drive and curiosity led her to think outside the box. She uncovered a way to find genetic material from the tumor in the aqueous humor, the fluid available at the front of the eye. This method (the liquid biopsy) allows clinicians to diagnose retinoblastoma more quickly and more accurately—on the molecular level. Dr. Berry’s research shows that the genetic information coming from the aqueous humor can actually help doctors predict which treatment a child might best respond to. Personalized medicine like this leads to better, more individualized care.

Dr. Berry’s discovery will have an impact beyond the patients she sees. The National Cancer Institute’s Pediatric Match program aims to better understand genetic alterations in all known pediatric cancers. Retinoblastoma—being rare and poorly understood on the genetic level—is not in this data repository. But that will likely change very soon.

This discovery wouldn’t exist if Dr. Berry wasn’t at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, which is one of the largest referral centers for pediatric eye cancers in the western United States. As a clinician, she grew frustrated with the limitations in diagnosis. This led her to study the problem and work toward a solution. “If I wasn’t seeing patients every day who needed something better,” she says, “this research would not have happened.”

Because who better than a pediatric surgeon to make care after surgery safer and more effective?

If Lorraine Kelley-Quon, MD, MSHS, were a chess player, she’d be the type to think multiple moves ahead. Although she’s a pediatric surgeon, she not only focuses on the immediate medical needs of her patients, but she also thinks about how to improve children’s recovery after surgery.

“My work extends beyond surgery to the child or adolescent healing at home,” she says. Dr. Kelley-Quon is making sure pain management is not only effective, but also safe.

While people don’t tend to think the opioid epidemic affects children and adolescents, it absolutely does, she says. Prescription opioid misuse and abuse in teens continues, due in part to the frequent prescribing of opioids after surgery. A few decades ago, opioids were rarely given to children for pain. Fast forward to 2018, when a staggering 1 in 10 adolescents were prescribed opioids. Along with continued sharing and recreational use of prescription opioids, there is an upward trend of teen deaths due to opioid-related overdose. To call today’s opioid problem a crisis is not hyperbolic.

It’s understandable that potential risks of pain meds are upstaged when families are managing something as big as their child’s surgery. Although opioids can help a child safely recover after surgery, they should be prescribed judiciously and not necessarily as the default when managing a patient’s pain. This is why Dr. Kelley-Quon led a team of health care providers and community advocates to establish the first-ever guidelines on the safe use of opioids in children.

“It’s not that opioids should never be prescribed,” she says. “We just want it to be done in a thoughtful and consistent way to minimize risks and maximize recovery.”

Eventually, we may see policy changes regarding prescription of opioids. For now, Dr. Kelley-Quon is laying the groundwork. And it wouldn’t be possible anywhere else.

“Being at a children’s hospital means thinking about one patient at a time,” she says, “focusing on each family with everything I have. But sometimes it also means thinking bigger—not only for the safety of our patients but for the safety of a child’s community, and for children across the country and beyond. It’s up to us and that’s why we work here.”

Learn about The Saban Research Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.