Heart—and Eyes—of a Champion

Noa stood at the starting line, slightly crouched down, right foot in front of the left. He was so nervous, he was shaking.

GO!

And they were off—eight middle school boys flying down the track in the afternoon sun. Noa was near the front of the pack, pumping his arms and legs furiously. Seconds later, he burst past the 50-meter finish line.

He had medaled: second place. YES! He broke into an impromptu victory dance. His friends and teammates ran up, excitedly giving him high fives.

His parents, Kaeko and Eric, cheered from the sidelines—and wiped the tears from their eyes. Thirteen years earlier, they had never dreamed Noa would be one of the fastest kids in his class.

They hadn’t even known if he would live at all.

Joy, fear and hope

Back in December 2004, when Kaeko realized she was pregnant with Noa, she and Eric did their own victory dance.

They had been trying to have children for years, but were losing hope. So when a pregnancy test came back positive—and they heard Noa’s heartbeat via an ultrasound test—“it was a miracle,” Kaeko says. “We were sooo excited.”

But several weeks later, another ultrasound turned their joy to fear. Something was wrong with their baby’s heart.

Noa had tricuspid atresia, a condition where the tricuspid valve does not form. Without this important valve, blood flow to the right ventricle is blocked. As a result, the right ventricle can’t grow and is severely underdeveloped—a condition called hypoplastic right heart syndrome.

Although the first specialist gave them a bleak prognosis, Kaeko and Eric began tenaciously researching and seeking different opinions. Eventually, they found Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“Children’s Hospital was so different,” Eric says. “They were like, ‘This is our expertise.’ They were very confident and walked us through what to expect. We felt like, OK, we have a plan now.”

‘How can I save him?’

In August 2005, Noa was born and immediately transferred to the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Fortunately, he didn’t need surgery right away, and Kaeko and Eric soon took him home.

Just three months later, they were dealt another devastating blow.

They both had noticed that every time they took a photo of Noa using a camera flash, his left eye would have a strange white glow in the picture. Worried, they told their pediatrician, who immediately sent them to The Vision Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

The diagnosis: retinoblastoma, a type of childhood eye cancer. Noa had tumors in both eyes.

Kaeko thought she would fall to the floor.

“It was more than shock,” she says. “I couldn’t even cry or be emotional. It was kind of like animal mother instinct: OK, what’s next? How can I save him? That’s how I felt.”

Being born with both hypoplastic right heart syndrome and retinoblastoma is extremely rare. Fortunately, the family had once again come to the right place. The Vision Center has been a pioneer in retinoblastoma treatment and research since 1987, when Children’s Hospital researchers identified the gene that causes the disease.

But before Noa could begin treatment, he needed heart surgery.

A different kind of storybook

In December 2005, Heart Institute Co-Director Vaughn Starnes, MD, performed the first of three surgeries to reconstruct Noa’s heart.

Soon afterward, Noa started systemic chemotherapy for his retinoblastoma. The chemo initially worked wonders on the tumors in his left eye. For his right eye, though, he also had to receive radiation therapy.

In addition, he had to go under anesthesia every few weeks—more than 30 times in all—for eye exams and focal laser treatments to “zap” residual tumors (a treatment pioneered at The Vision Center).

“We were almost living at Children’s Hospital,” Kaeko says. “Noa was a famous guy there. Everyone knew Noa!”

Meanwhile, Dr. Starnes performed two more open-heart surgeries on Noa. The last one came at age 3. At that point, Noa’s retinoblastoma was in remission. They were almost out of the woods.

But shortly before his 4th birthday, the tumors in the left eye began to return. There was only one option now: removing the eye.

He had never been able to see out of that eye. Still, his parents were reeling. And they faced a gut-wrenching task: How do you tell your 4-year-old that he’s going to lose his eye?

They followed an idea from Nancy Mansfield, PhD, then a counselor who supported families in the Retinoblastoma Program. (Dr. Mansfield passed away in 2010.)

“We made a little book and cut out pictures, so each page had a picture with some simple words,” Eric recounts. He stops and takes a drink of water. Reliving this moment is hard. “We read it like a storybook to him—showing that the eye was sick, and you take the eye out, and he’s going to be all better.”

The last page? A picture of Disneyland. “We let him know that after all this was done, he’d be going to Disneyland,” he adds, then starts to cry. “He was really happy about that.”

‘Just a normal guy’

Noa, now 14, didn’t expect himself to get second place in that 50-meter dash last year. And at that same inter-school meet, he helped his team win a bronze medal in a relay race.

“I like running,” he says. “It’s a little hard for me doing the long distance. But the short distances are fun.”

Sarah Badran, MD, his cardiologist at Children’s Hospital L.A., says his heart is doing great.

“I am in disbelief at how he did in that race,” Dr. Badran says. “Noa is an amazing kid. He’s got such a strong spirit. He really pushes himself.”

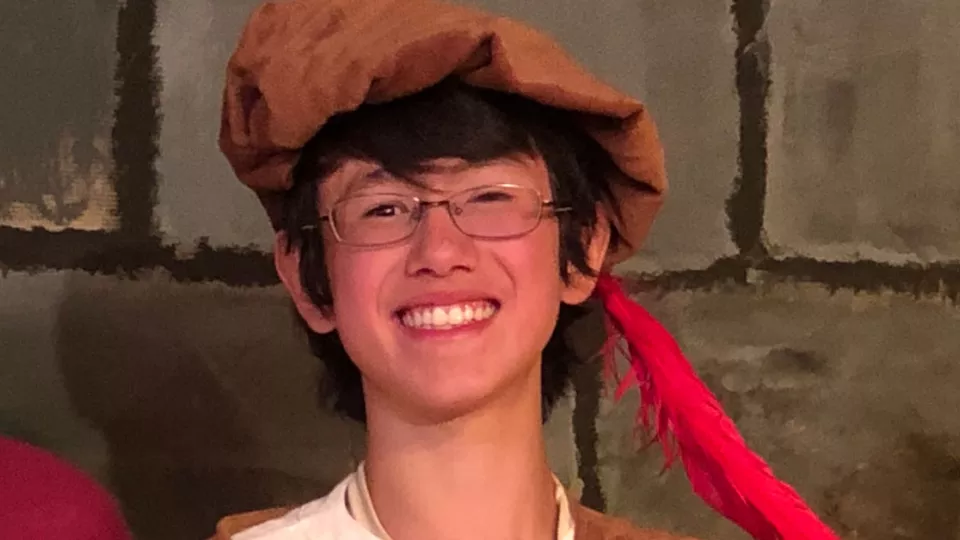

Running is just one of Noa’s pursuits. He also likes karate and baseball, has played piano for eight years and lately has taken up acting. He played Don Quixote’s sidekick, Sancho, in the school play last year—singing two songs solo onstage—and got rave reviews.

The eighth grader has big plans, too. “I want to go to MIT and become a computer engineer,” Noa says. “Oh, and I’ve built a computer before! That was really cool.”

And what about all those heart surgeries and the eye removal? He has no memory of most of it. He’s been cancer-free for more than 10 years, and his prosthetic eye—he calls it his “special eye”—is so realistic-looking, his dad sometimes forgets which eye is the “real” one. With his glasses, he has 20-20 vision.

“Children do very well with one eye if they have good vision in that eye,” explains Jonathan Kim, MD, Director of the Retinoblastoma Program at Children’s Hospital L.A. and Noa’s eye doctor since 2013. “With the exception of becoming a fighter pilot, he can do anything he wants.”

The Vision Center continues to spearhead research and recently pioneered the study of a liquid biopsy for retinoblastoma. Soon, it will begin a clinical trial to test a less-invasive device for delivering chemotherapy to the eye (for patients who only have retinoblastoma in one eye).

The device was developed by Noa’s first eye doctor, A. Linn Murphree, MD, who founded the Retinoblastoma Program and has since retired from Children’s Hospital.

Noa and his parents are grateful to so many people, including Dr. Murphree, the late Dr. Mansfield, and Noa’s current doctors—Dr. Badran, Dr. Kim and oncologist Rima Jubran, MD.

“Sometimes we forget he had to deal with these hard health issues,” says his mom. “He’s just a normal, regular guy!”

Noa has some simple advice for other kids facing an eye removal.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “I’m living a really happy life, and a normal one. What’s most important is to be alive and healthy.”

How you can help

To help kids just like Noa, consider making a donation to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Visit CHLA.org/Donate.