Nature, Nurture, and Neurodevelopment

CHLA’s Dr. Bradley Peterson weighs in on what it takes to develop a human brain

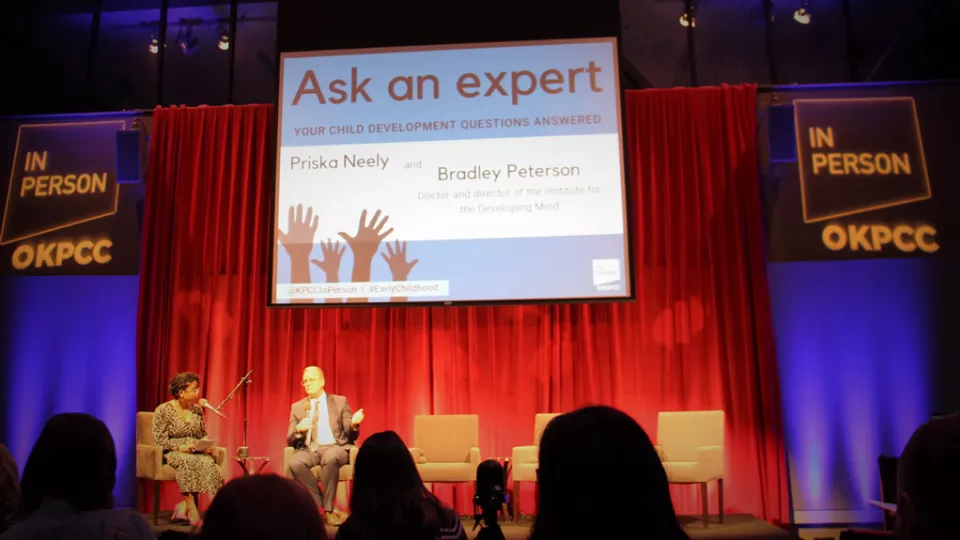

In a public town-hall style event, CHLA’s Dr. Bradley Peterson spoke amongst a panel of early childhood specialists. The event was organized by KPCC In Person and hosted by Priska Neely, who covers early childhood and the issues young children face.

In addition to Peterson, the well-rounded panel of four included author Roma Khetarpal, UCLA pediatrician Adam Schickedanz, and early childhood education expert Schellee Rocher. Each panelist spoke one-on-one with Neely before fielding a wide range of parenting questions from the audience.

Designated by Neely as the “brain guy,” Peterson painted an elaborate picture for the event’s host and the audience about neurodevelopment. “You can think of the developing brain as a sphere,” he began. “A cross-section of this sphere through its middle might resemble a bicycle wheel. It’s organized with spokes radiating outward towards the tire, or surface of the brain.” Peterson likened these spokes to neurons. “Neurons are the brain cells that pass information and allow us to think, behave, and have emotions,” he explained.

Peterson went on to say that, at birth, the architecture of the brain is very sparse compared to what it will soon become. Soon after birth, he said, the brain cells begin to sprout and grow dendrites – the branching, bushy structures that receive information from other brain cells. Cells begin to connect to one another, forming dense, complex circuitry. “Unbelievably quickly,” Peterson continued, “in the first months of life, the spokes begin to fill in.” The architecture of the brain is being built at lightning speed in this first year of life. It is this growing complexity, he said, that allows new information to be passed from one part of the brain to another. This dense web of interconnected brain cells sets the very foundation of all emerging capacities in early childhood – things like walking, talking, thinking, and relating socially to others.

Sometimes, the brain is compared to a computer. This analogy speaks to the brain’s incredible computational capacity, though it does not acknowledge some of its more mysterious aspects– things like personality or a person’s ability to love. Peterson expanded upon the intrigue of the brain’s capabilities, explaining that the ability to learn and physically reshape itself sets it apart from its machine counterpart. “A one-year-old is just beginning to walk and say a few words. In the next year or so, that child will be capable of hundreds of words. No computer can teach itself to do that. This ability is all due to the developing architecture of the human brain.”

This ability to learn can be found in our DNA long before a brain even begins to develop. Written into the very code from which all our proteins, cells, and tissues are born is the ability of the brain to be molded by our surroundings, a stunning feat of adaptability. Unlike a computer, the human brain grows and learns in a way that is largely dependent upon experience, which actually shapes the physical architecture of the brain. Peterson explained that the dense, bushy web of interconnected cells in a two-year-old’s brain is actually richer in connections than in an adult’s brain – 50% more dense. The environment, he said, guides the brain in which connections will survive and become permanent, while pruning the irrelevant circuits. “It’s a dance between the developing organism, with all its hard-wired programming, and the environment – each interacts with, and affects, the other.” What we are left with is imagery of a blossoming array of neural connections that begins to explode within the first two years of life, and is then masterfully whittled away as we are shaped by our experience. The mature brain is perhaps less a computer than it is a sculpted work of art made by our genes and the world that surrounds us.

Click here to visit the KPCC In Person event page with full video of event.