CHLA Receives $1.5 Million Grant to Help Expand Pediatric MRI Access to Developing Countries

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used in pediatric neurology because it can accurately measure brain tissue and structure to diagnose conditions such as early ischemic brain injury, as well as investigate brain development. MRI can also be used to identify alterations associated with neurologic, psychiatric, developmental and learning disorders and evaluate the impact of interventions.

But until recently, MRI has only had been in widespread use by hospitals and research institutions in developed countries. “If you buy a scanner in the developed world, you will buy a high-field system of 1.5T or above,” says Natasha Lepore, PhD, Associate Professor of Research at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “You need specific infrastructure for it, so it's very expensive and maintenance is high. Putting a multimillion-dollar machine in a developing country is not really feasible.”

Recent innovations in imaging technology have led to the development of low-field 0.064T MRI scanners that are more accessible for low-resource countries. “These low-field MRI systems cost in the hundreds of thousands, rather than in the multiple millions of dollars, and are cheaper to operate and maintain,” says Dr. Lepore, also an Associate Professor of Research Radiology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “They are small enough to put in a van. They can be rolled around and plugged into the wall. It's a way to bring both research and clinical imaging to the developing world by lowering the cost and improving accessibility.”

An international research collaboration led by Dr. Lepore has received a three-year $1.5 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop standardized tools to make low-field MRI useful for pediatric brain research. The project is part of a larger initiative supported by the Gates Foundation to empower the use of low-field scanners for research in low-resource settings. These scanners will be used in studies on the effects of malnutrition on brain development, as well as on mothers who become anemic when breastfeeding after birth. The studies may help to characterize the early neurodevelopmental patterns of infants in different geographic areas, identify the primary factors that impair children’s growth and brain development, and evaluate the impact of different maternal and infant-focused interventions to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes. “This is a huge worldwide collaboration,” says Dr. Lepore.

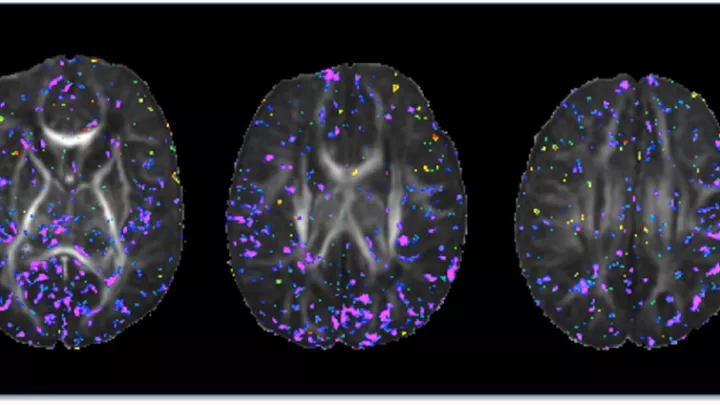

Over the last year and a half, the Gates Foundation has funded the installation of 25 low-field MRI systems in physics and engineering centers in developed countries, as well as at clinical partner sites in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. “Instead of 3T, their scanner is 0.064T, which solves a number of problems,” says Dr. Lepore. “But as the quality of the image depends in part on the strength of the magnetic field, the image is of lower quality.” The smaller magnetic field means that this technology requires specialized image processing tools to boost its resolution. Moreover, infant brain tissue is more challenging for low-field systems to image than that of adults, as it is harder to distinguish between different types of tissues, and infant brains also change rapidly in the first years of life. The team will produce a suite of standardized clinical image analysis software for the use of the global MRI community.

Dr. Lepore, the Principal Investigator on this project and long-time collaborator, Marius George Linguraru, DPhil, MA, MSc, site Principal Investigator at the Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation at Children's National Hospital in Washington, D.C., will analyze data on the brains of children from birth for the maternal and health studies. This MRI data will form the basis for future studies of children’s brain anatomy in health and disease.

This grant will also support training local teams in methods and approaches with the aim of building research capacity to pursue joint projects in pediatric health, starting with recruiting a research team in Uganda to perform a long-term infant brain development study and analyze data collected by the MRI scanners.

“MRI provides information on the consequences in children’s brains of malnutrition or neglect because of poverty,” says Dr. Lepore. “Having scanners on-site means that researchers can see the challenges specific to various geographic regions and demographics and their consequences on the brain to better guide social and clinical interventions. Moreover, in many of these countries, there's a shortage of specialists and so having automated processes to analyze images is essential to assist in interpreting them.”