CHLA Scientist Awarded $1.2M to Study Drug Resistance in Leukemia

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is the most prevalent childhood cancer, with more than 3,000 new cases reported each year. The majority of patients with ALL survive following chemotherapy treatments but some patients do not respond well, experiencing drug resistance and relapses in the disease. The most common cause of these unsuccessful outcomes? A researcher at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles says the answer lies in a patient’s own bones.

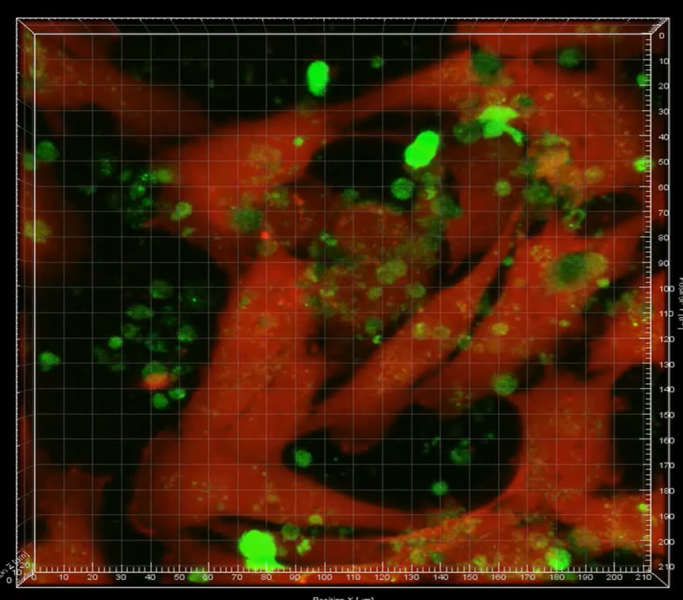

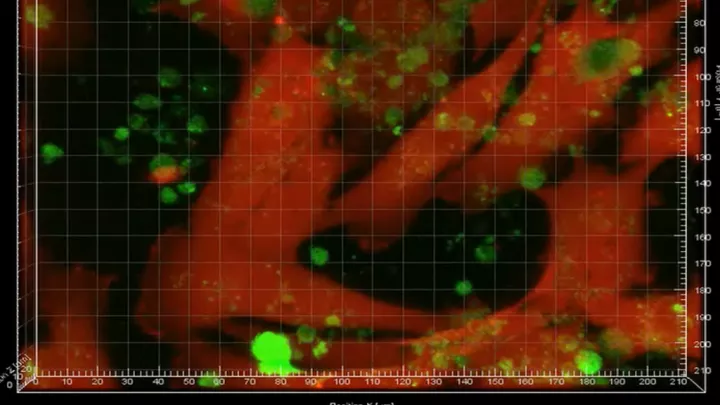

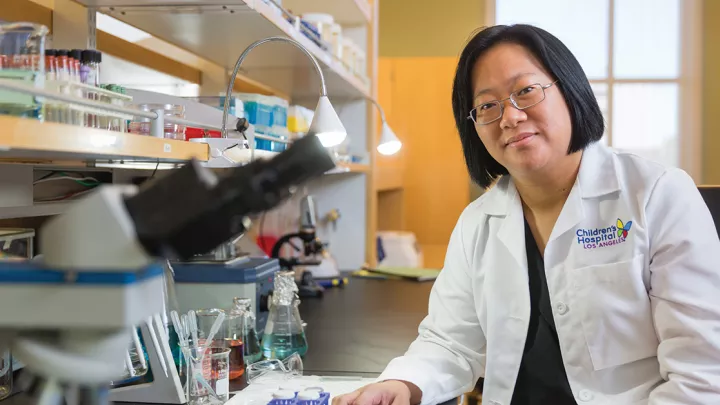

Yong-Mi Kim, MD, PhD, MPH, an investigator in the Children’s Center for Cancer and Blood Diseases at CHLA, explains how leukemia cells can hide in bones. “Most relapse occurs in the bone marrow,” Kim says, “where the tissue harbors the leukemia cells and provides a safe haven that shelters them from chemotherapy.” It is known that bone marrow cells called stromal cells are responsible for shielding the cancer. “The question is, really, how they do it,” she says.

Kim, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics in the Keck School of Medicine of USC, leads a research team in studying a type of molecule called integrins, which are responsible for keeping many cells in the body fixed in their proper places. Her lab was the first to discover that one of these integrins, integrin alpha 4, anchors leukemia cells in the bone marrow, allowing them to become resistant to treatment. Because of this, she explains, ALL cells can hide, lying dormant in the bone marrow for years before causing a dangerous, often deadly, relapse in the disease. For this reason, Kim feels it is a mistake to look only at the cancer cells in leukemia research.

“Our lab is different from others because we try to see things from the perspective of the microenvironment,” Kim says. Now that she has established a role for integrin alpha 4, she aims to uncover other integrins that likely work in concert to shield ALL cells from chemotherapy. Once all the key players are identified, treatments can be devised to block the activity of these integrins, so leukemia will have nowhere to hide. Kim’s grant, which was funded by the National Institute of Health’s National Cancer Institute, will help her to pinpoint which integrins will make for the best treatment targets. “We want to harness this knowledge, target these molecules, and eventually make it to a clinical trial,” Kim explains.

Chemotherapy comes with a long list of side-effects and possible long-term effects. Still, no one can doubt the high success rate in pediatric patients, estimated to be about 85-90%. But Kim does not find this to be acceptable. “Overall, children do very well but we are still failing around 10-15% of them,” she says, “and every child counts.”

About Children's Hospital Los Angeles

Children's Hospital Los Angeles has been ranked the top children's hospital in California and sixth in the nation for clinical excellence by the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll. The Saban Research Institute at CHLA is one of the largest and most productive pediatric research facilities in the United States. CHLA also is one of America's premier teaching hospitals through its affiliation since 1932 with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. For more, visit CHLA.org, the child health blog and the research blog.