Left to right: Paul S. Viviano, President and Chief Executive Officer of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; Alan S. Wayne, MD, Director of the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at CHLA; and Lara Khouri, MBA, MPH, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of CHLA, at the grand opening of the cGMP Laboratory.

New cGMP Facility Aims to Accelerate Cell Therapy for Pediatric Cancer

Earlier this year, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles celebrated the opening of the USC/CHLA cGMP Laboratory, a 3,184-square-foot facility that will manufacture cell and gene therapies under the Food and Drug Administration’s current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) standards.

The lab—a partnership between Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck Medicine of USC and the Keck School of Medicine of USC—aims to accelerate next-generation cell therapy and advance early-stage research into lifesaving, commercially viable treatments.

In addition, CHLA and the Keck School of Medicine of USC were recently awarded an $8 million grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to expand access to cell and gene therapy clinical trials.

What impact will this new facility have on children with cancer? Four physician-scientists in the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at CHLA share how they are working to make cell therapy more effective—and accessible—for pediatric patients.

A gated approach to AML

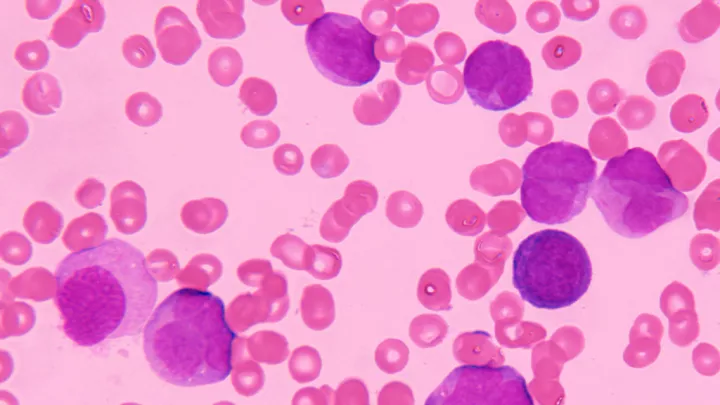

In recent years, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has revolutionized treatment for patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). But unfortunately, CAR T-cells have been less effective for some other leukemias—including acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

A key problem, explains Babak Moghimi, MD, is that the antigens that CAR T-cell therapy needs to target on AML cells are also expressed on normal blood cells—making the treatment too toxic. To work around this obstacle, Dr. Moghimi has been engineering “gated” CAR T-cells that target two tumor antigens, not just one.

“I make T-cells that have a logical circuit in them, like a computer,” he explains. “You tell the T-cells: ‘Only kill the cells that are positive for antigen A and antigen B.’ By requiring that both antigens are present, you can focus the T-cells on the cancer, while significantly decreasing the chances that they will also destroy normal cells.”

Dr. Moghimi and his team are studying a similar approach for solid tumors as well. In AML, they have developed SynNotch gated T-cells that target CD33 and CD123—two antigens expressed by virtually all leukemia cells. The team has completed those preclinical studies and is applying for grants to support a potential clinical trial.

The cGMP facility will play a key role in making such a trial possible. “It gives us the capability to manufacture the T-cells we would need to test this therapy in patients,” Dr. Moghimi says. “That will significantly reduce the costs and time needed to develop a clinical trial, making it more feasible. It’s a critical step.”

Supercharging CAR-T for solid tumors

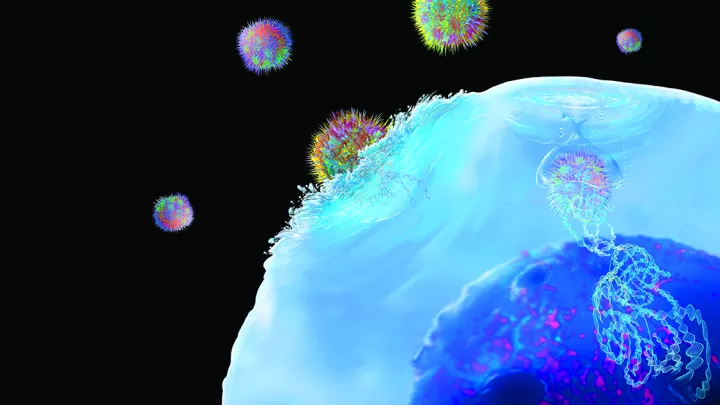

Why do CAR T-cells have so much trouble killing solid tumors? “I think about that question almost every day,” says Sarah Richman, MD, PhD. “And we don’t have an answer.”

It could be, she says, that more aggressive T-cells are needed to penetrate the 3D bulk of a solid tumor. There’s also the problem of the tumor microenvironment—the cells surrounding the tumor that cleverly disarm and exhaust any advancing T-cell army. And then there’s the issue of toxicity—making sure that CAR-T cells don’t destroy normal tissue.

Dr. Richman’s research is focused on “supercharging” CAR T-cells so they can overcome these challenges. One approach she and her team are studying is to combine CAR T-cells with small molecule anti-cancer drugs. The idea: weaken the tumor or slow its growth to give T-cells a better chance to succeed.

In addition, her group recently began collaborating with Peter Yingxiao Wang, PhD, Chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at USC. Dr. Wang and his colleagues have developed a way to use focused ultrasound to remotely control the activity of specially engineered CAR T-cells—allowing them to more precisely target solid tumors, while reducing toxic side effects.

Although the team is just beginning preclinical studies, she notes that the cGMP facility will be essential to moving future discoveries from the bench to the bedside.

“Many children with solid tumors don’t respond to standard treatments; they desperately need new and innovative approaches,” she notes. “This facility will be a tremendous help in bringing more early-phase trials to these patients.”

Making remissions last

One year after receiving the only currently FDA-approved CAR T-cell therapy for pediatric ALL, there’s a stark divide between patients: Half are still in remission, but the other half have relapsed.

“My research is focused on better predicting which children will relapse and which ones will stay in remission after CAR T-cell therapy,” says Emily Hsieh, MD. “And then, for those children who are at high risk, what treatments can we provide to help keep them in remission?”

To achieve this goal, Dr. Hsieh is investigating how tools that can more sensitively detect leukemia cells (such as next-generation sequencing techniques) can guide providers during the monitoring period. The idea is to be able to decipher who is at high risk for relapse—and may need a bone marrow transplant—and who would benefit from a “watch and wait” approach.

She is also evaluating potential treatments to prevent relapse after CAR T-cell therapy—including administering CAR T-cell re-infusions before a patient relapses or administering low-level chemotherapy to high-risk CAR T-cell patients.

A clinical researcher and a site principal investigator for several CAR T-cellular therapy trials at CHLA, Dr. Hsieh will serve as a vital bench-to-bedside liaison for researchers.

“My role is to be that translational link connecting the lab to the clinic,” she says. “The cGMP facility is a crucial step in this process. I can’t overstate how much it will accelerate CAR T-cell development and translation.”

Improving access for families

Cell therapy clinical trials can offer a lifeline of hope for children with relapsed or treatment-resistant cancers. But not all patients are able to access these trials.

Improving that access for families from diverse and underrepresented communities is the goal of Paibel Aguayo-Hiraldo, MD, Clinical Director of the Transplant and Cellular Therapy Program at CHLA. She is a site principal investigator for a multicenter study that is examining how to remove the barriers to trial participation for these families.

Recently, the group published a paper showing that Hispanic, Spanish-speaking and publicly insured patients are underrepresented in referrals from outside hospitals to CAR T-cell centers.

“One barrier is that families can be hesitant to participate in research,” Dr. Aguayo-Hiraldo explains. But the study also found that patients enrolled in CAR T-cell therapy trials lived closer to a CAR T-cell center, and providers may consider factors besides medical eligibility when considering whom to refer for these trials.

“Several immunotherapy trials will cover transportation and/or lodging costs,” she says. “But community physicians may not be aware of this, and so they may not take it into consideration when deciding on patient referrals.”

The group is now conducting more interviews with community providers to better understand these challenges. “Here at CHLA, we build partnerships with our community and out-of-state physicians,” she adds. “That allows us to bridge that gap—improving providers’ familiarity with trials and helping their patients access these potentially lifesaving therapies.”

And while CHLA is a participating site in several cell therapy trials, the addition of the cGMP facility will help bring more trials to the hospital—and its diverse patient population.

“It’s so important to have this facility at a place like CHLA, where a large percentage of our patients come from diverse and underserved communities,” Dr. Aguayo-Hiraldo says. “My hope is that it will improve access to novel therapies and ultimately, outcomes for all patients. That is the biggest goal.”