Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy: What Physicians Should Know

Brachial plexus injuries in infants affect the nerves that provide sensation and movement in the shoulder, arm, forearm, hand and fingers. These injuries are also referred to as Erb’s palsies or neonatal brachial plexus injuries. Incidence is between 0.4 and 4 in 1,000 live births.1-3

Risk factors include:

- Shoulder dystocia (baby’s shoulder gets stuck exiting the birth canal)

- Prolonged labor

- Macrosomia (birth weight more than 4000g)

- Instrumented delivery (use of forceps, vacuum)

- Excessive maternal weight gain, gestational diabetes

- Presence of clavicle or humerus fracture at birth

What happens in a brachial plexus injury?

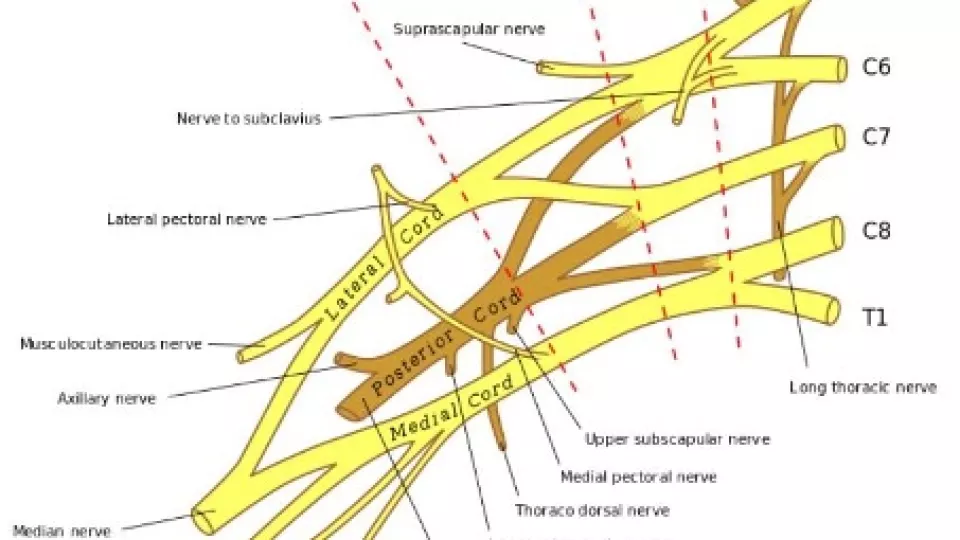

The brachial plexus is made up of the nerves coming from the spinal cord from C5 to T1. These nerves branch out and continue down into the shoulder, arm and fingers.

When the head is stretched away from the shoulder during birth, the nerves that make up the brachial plexus might stretch or tear (rupture). The injury may also pull the nerves’ roots off of the spinal cord (called root avulsion). This results in loss of motor and sensory function of the involved arm.

What are the signs of a brachial plexus injury?

Signs of a brachial plexus injury usually include:

- Asymmetric movement and resting position of the affected arm (typically the arm is extended and internally rotated at the shoulder with the wrist in flexion “waiter’s tip position”).

- A droopy eyelid and smaller pupil on the affected side (a Horner’s sign)

How is a brachial plexus injury treated?

Babies with suspected brachial plexus injuries benefit from early diagnosis and treatment. Early consultation with a specialized team consisting of peripheral nerve surgeons (orthopaedic, neurosurgery or plastics-trained) and neurologists, along with occupational/physical therapists who specialize in the treatment of these injuries is critical and offers the best chance to maximize the baby’s recovery.

In some cases, surgical treatment may be recommended in order to help restore neurologic function. Most surgeries are done in the first year of life, as early as 3 months of age in the most severe cases.4 Early surgical treatments may include:

- Nerve grafts: A nerve from another area of the body, usually from the back of the leg, is used to bridge across an injured nerve segment.

- Nerve transfer: A part of a healthy nerve is “transferred” to a muscle that has lost its innervation.

After these types of surgery, recovery may take up to several years and continued involvement by a team of brachial plexus specialists is very important. Sometimes additional surgery such as moving tendons and muscles around is necessary to help children achieve their full neurologic potential.

When to refer?

While there are no set criteria for referral, the earlier the better! Any asymmetric upper extremity movement should be evaluated to rule out a brachial plexus birth palsy. The classic teaching was that 92% of patients with brachial plexus birth palsy have a mild injury and recover within the first few months of life without needing surgery.5 More recent studies have shown less optimistic numbers, with 66% recovering spontaneously and between 10-15% left with permanent weakness.2,6

References

- Foad SL, Mehlman CT, Ying J. The epidemiology of neonatal brachial plexus palsy in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg 2008; 90A:1258–1264.

- Hoeksma AF, ter Steeg AM, Nelissen RG, van Ouwerkerk WJ, Lankhorst GJ, de Jong BA. Neurological recovery in obstetric brachial plexus injuries: an historical cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46:76–83.

- Waters PM. Obstetric brachial plexus injuries: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1997;5:205–214.

- Hale HB, Bae DS, Waters PM. Current concepts in the management of brachial plexus birth palsy. Journal of Hand Surgery 2010;35A:322-331.

- Laurent JP, Lee R, Shenaq S, Parke JT, Solis IS, Kowalik L. Neurosurgical correction of upper brachial plexus birth injuries. J Neurosurg 1993;79:197–203.

- Pondaag W, Lee R, Shenaq S, Parke JT, Solis IS, Kowalik L. Natural history of obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46:138–144

About the Authors

Susan Durham, MD, MS

Chief, Division of Neurosurgery

J. Gordon McComb Family Chair of Pediatric Neurosurgery

Attending Surgeon, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

Professor of Clinical Neurological Surgery, Keck School of Medicine of USC

Leigh Maria Ramos-Platt, MD

Director, Muscular Dystrophy Association Neuromuscular Clinic

Attending Physician, Division of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

Associate Professor of Clinical Neurology, Keck School of Medicine of USC

Erin Meisel, MD

Director, Brachial Plexus Program; Attending Surgeon, Children’s Orthopaedic Center, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

Assistant Professor of Clinical Orthopaedic Surgery, Keck School of Medicine of USC