Definition

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a devastating disease that affects mostly the intestine of premature infants. The wall of the intestine is invaded by bacteria, which cause local infection and inflammation that can ultimately destroy the wall of the bowel (intestine). Such bowel wall destruction can lead to perforation of the intestine and spillage of stool into the infant’s abdomen, which can result in an overwhelming infection and death.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Overall, NEC affects one in 2,000 to 4,000 births, or between one percent and five percent of neonatal intensive care unit admissions. The disease occurs in nearly 10 percent of premature infants but is rare in full term infants. Although the exact cause of NEC is still unknown, there are many theories to explain why NEC affects mainly premature infants. The only consistent observations made in infants who develop NEC are the presence of prematurity and formula feeding. The premature infant has immature lungs and immature intestines. Therefore, any decrease in oxygen delivery to the intestines, because the lungs cannot oxygenate the blood adequately, will damage the lining of the intestinal wall. This damage to the bowel wall will allow bacteria that normally live inside the intestine to invade the wall of the intestine and cause local infection and inflammation (NEC) that can eventually lead to rupture or perforation of the intestine.

Clinical Presentation

NEC typically develops within the first 2 weeks of life in a premature infant who is being fed with formula as opposed to breast milk. One of the first signs of NEC is the inability of the infant to tolerate the feedings. This is often associated with abdominal distention (bloating) and vomiting bile (green). The infant may also have bloody stools because of the infection of the bowel wall. If the infection is not recognized early, then the child may develop a low respiratory rate or periodic breathing (apnea) and a low heart rate that may necessitate insertion of a breathing tube. Other findings may include a red and tender abdomen (see Figure 1), diarrhea, lethargy (listlessness) and shock (decreased blood pressure).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of NEC is usually confirmed by the presence of gas or air bubbles in the wall of the intestine on an abdominal X-ray (see Figure 2A). Other radiographic findings may include the presence of air bubbles in some of the veins that go to the liver, or the presence of air outside of the intestines in the abdominal cavity (see Figure 2B). Blood tests may reveal a decreased number of platelets, which normally help form blood clots and prevent bleeding, and a decreased number of white blood cells, which normally help fight bacterial infections. These findings put the infant at risk for bleeding and serious systemic infection.

Treatment

The majority of infants with NEC are initially treated medically and symptoms often resolve without requiring surgery. Initial treatment of NEC consists of the following:

- Discontinue the feedings

- Insert an orogastric tube (a tube that goes from the mouth to the stomach to remove air and fluid from the stomach and intestine)

- Administer intravenous fluids and antibiotics

- Perform frequent, serial examinations and X-rays of the abdomen

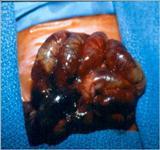

Infants who respond to this treatment often can resume feedings by mouth when signs of the infection have disappeared. This may take up to 5-7 days in some cases. Infants who have more severe disease may require a longer period for the return of bowel function, which is determined by the presence of normal bowel movements. Infants who do not respond to medical treatment and develop worsening condition or bowel perforation will require surgery. At the time of surgery, the surgeon may find portions of the intestine with gas bubbles in the intestinal wall (see Figure 3A), or portions of the intestine that is frankly necrotic (dead) or perforated (see Figure 3B).

The operation consists of removing the piece of intestine that has ruptured or is about to rupture. The surgeon tries very hard to preserve as much intestine as possible by removing only the segments that appear to be frankly dead or have ruptured (see Figure 3B). In most instances, especially if the baby is very sick (in shock for instance) or if there is extensive spillage of stool in the abdomen, the surgeon may decide to bring out a viable piece of proximal intestine (the segment of intestine that is located closest to the stomach) to the abdomen in order to avoid continued spillage of stool in the abdomen; this is known as an ostomy. In this instance, the baby will poop out of the stoma instead of spilling stool into the abdomen. The stoma should allow sufficient time for the baby to recover from the infection with the help of antibiotics and other treatments. If the child recovers, after six to eight weeks, he can be brought back to the operating room to undergo reversal of the stoma to restore continuity of the bowel so that the poop will come out of the anus once again.

Prognosis

Most infants who develop NEC recover fully and do not have further feeding problems. In some cases, scarring and narrowing of the bowel may develop and can lead to future intestinal obstruction or blockage. Another residual problem may be malabsorption (the inability of the bowel to absorb nutrients normally). This is more common in children who require surgery for NEC and lose a large segment of intestine. Still, there are some infants who lose so much intestine from the infection that they do not have enough intestine left to survive. These infants may end up requiring a bowel transplant to survive.

Future Therapy

There are many exciting prospects on the horizon to try to treat or prevent NEC. Some of the more promising treatments include administration of probiotic (“good”) bacteria to premature infants to oppose the effects of the pathogenic (“bad”) bacteria that cause the infection. Other promising treatments that we have come up with from the research done in our laboratory include blocking the production of a substance known as nitric oxide, which is produced in high quantity during NEC and contributes to the destruction of the bowel wall. Also, very small quantities of carbon monoxide, the same gas that comes out of the muffler of automobiles or from cigarette smoke, appear to protect baby rats from developing a "rat form" of NEC (intestinal inflammation), by decreasing production of nitric oxide.

References

Chokshi NK. Guner YS. Hunter CJ. Upperman JS. Grishin A. Ford HR. The role of nitric oxide in intestinal epithelial injury and restitution in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. [Review] [88 refs] Seminars in Perinatology. 32(2):92-9, 2008 Apr.

Hunter CJ. Upperman JS. Ford HR. Camerini V. Understanding the susceptibility of the premature infant to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). [Review] [109 refs] Pediatric Research. 63(2):117-23, 2008 Feb.

Ford HR. Mechanism of nitric oxide-mediated intestinal barrier failure: insight into the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. [Review] [45 refs] Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 41(2):294-9, 2006 Feb.

Zuckerbraun BS. Otterbein LE. Boyle P. Jaffe R. Upperman J. Zamora R. Ford HR. Carbon monoxide protects against the development of experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal & Liver Physiology. 289(3):G607-13, 2005 Sep.

Hunter CJ, Chokshi N, Ford HR. Evidence vs experience in the surgical management of necrotizing enterocolitis and focal intestinal perforation. J Perinatol. 2008 May;28 Suppl 1:S14-7.

Hunter CJ, Podd B, Ford HR, Camerini V. Evidence vs experience in neonatal practices in necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol. 2008 May;28 Suppl 1:S9-S13.