Pediatric AIDS - Then and Now

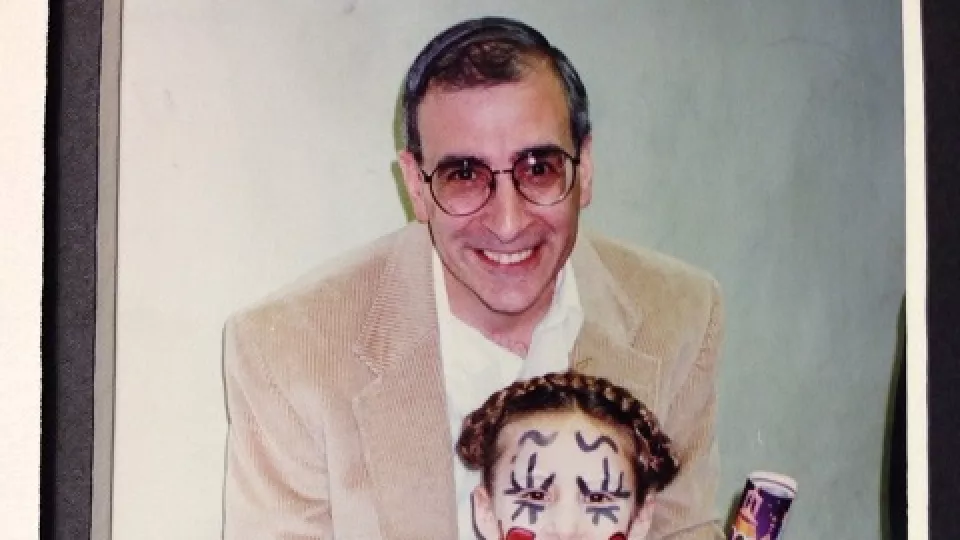

Joseph Church, MD, has a thick stack of programs from children’s funeral services in his office. But this story doesn’t have a sad ending.

“I remember every child I’ve treated who died of AIDS, and the ones who are living,” says Church, who is now division chief of Allergy and Immunology at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The reason he can tell this story now, with a smile, is that cases of HIV/AIDS in children in Los Angeles County are on a steep decline “thanks to research, and to the heroic measures of physicians at LA County Hospital, UCLA and other hospitals in treating moms-to-be who have HIV so they don’t transmit it to their babies.”

In 1981, AIDS was first described in the medical literature. “By 1982, it was pretty clear we were looking at a disease transmitted by a virus,” Church says. Within a year, the first child with AIDS was seen at CHLA, a one year old who had gotten the disease through a blood transfusion he received when born prematurely. The baby only lived a few more weeks.

In the early days, health care providers at CHLA donned gowns, gloves and masks to care for children with AIDS, even though many doctors, including Church, understood that the disease was not transmitted casually. “I learned a lot about fear in dealing with the disease.”

CHLA was one of the few places where these kids were being treated, and in the early to mid-80s, the sickest of them in Los Angeles Country came here. “Then, the majority of children with AIDS got it through a blood transfusion, but within a few more years – with blood being screened for the virus – we saw more babies contracting HIV/AIDS from their mothers before or during birth.”

Some with the HIV virus lived only a few months; others a few years or even decades. Church and other doctors in the Division of Immunology at CHLA – rather than their colleagues in Infectious Diseases – saw these children because of their immune deficiencies, and because at the time immunologists were more accustomed to successfully treating kids on an out-patient basis.

The incidence of HIV peaked in 1993 with 75 reported new cases in LA County. By 2007, this number had dwindled to six, despite the fact that AIDS had increased among females. A contributing factor to the decline in new pediatric AIDS cases is the increasing use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) since 1995 in HIV-infected children who haven’t progressed to AIDS, as well as providing such treatment to HIV-infected pregnant women.

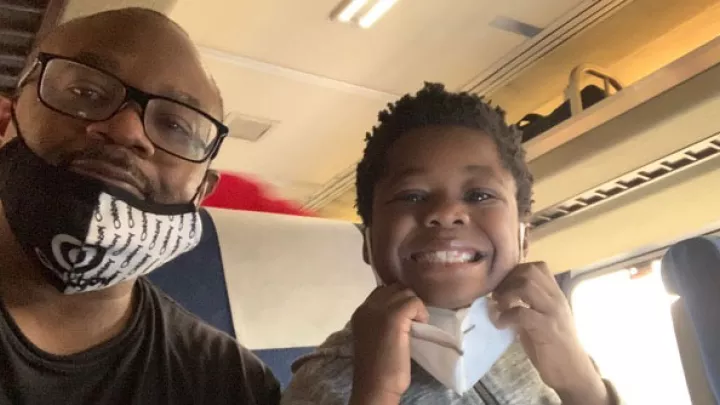

“In the last five years, only three babies have been born with HIV in LA County,” Church reports. Instead of the projected 60 patients a year without effective treatment, he now sees “maybe two.” He continues to care for a total of 45 children with HIV, all of whom have a good prognosis to live long and healthy lives.

But he hasn’t forgotten the 200 babies and young children who died at CHLA in the years before a treatment was discovered. Touching the red ribbon pin on his lapel, Church says, “I’ve worn this every day since 1992.” Now, it’s not only a symbol of young lives lost, but of hope that pediatric AIDS will be eradicated in his lifetime.