Management of Sickle Cell Disease: A Perspective for Pediatricians

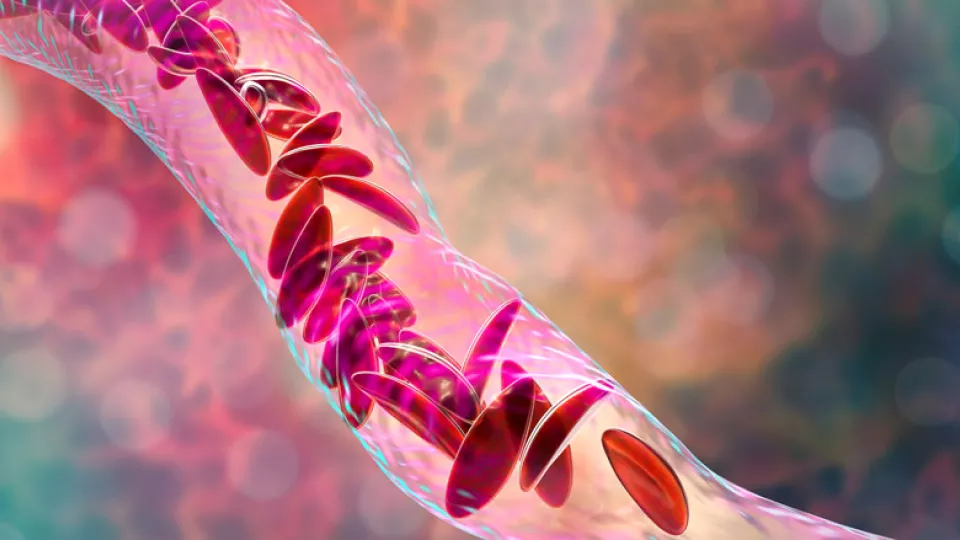

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic blood disorders, affecting over 100,000 Americans and 1 in 365 African-American newborn babies. It is an autosomal recessive condition, where homozygous or compound heterozygous individuals develop complications due to abnormal hemoglobin S, leading to rigid, sickle-shaped red blood cells that can obstruct microvascular blood flow. Hemoglobin SS, SC and SBeta0 thalassemia and SBeta+ thalassemia are the most common genotypes of SCD seen in the United States. Repeated vaso-occlusion with subsequent ischemia and increased hemolysis lead to organ damage and premature death. The median survival in the United States for SCD has greatly increased from approximately 12 to 15 years in the 1970s, and most children now are surviving into adulthood and some into their late 50s. This improvement in survival is mainly due to early diagnosis via newborn screening, institution of penicillin prophylaxis, pneumococcal vaccination, hydroxyurea as disease-modifying therapy and screening for stroke. Although survival has greatly improved, morbidity remains significant for the pediatric population, and optimally they require disease management and routine health monitoring for chronic organ damage at a comprehensive sickle cell clinic. Early recognition and intervention for acute complications is also key to improving outcomes, as patients’ clinical conditions can deteriorate rapidly during these events. This can be achieved through educating families and a collaborative approach from primary care and specialist providers. This article highlights some of the common acute complications that patients with SCD face and their management.

Infectious risk

The spleen is particularly prone to sickling and vaso-occlusion in SCD, and splenic dysfunction begins as early as 3 months of age and by 3 years most patients undergo “autosplenectomy” or fibrosis of the spleen. The spleen is the first line of defense against encapsulated bacteria, and thus SCD patients are at very high risk of septicemia and meningitis from pneumococcus, in particular. The advent of antibiotic prophylaxis and immunization has significantly improved mortality from pneumococcal sepsis, but significant risk still exists from resistant organisms, incomplete vaccination, etc. The following recommendations are adapted from evidence-based guidelines to decrease infectious risk in SCD.

- Oral penicillin prophylaxis twice daily (125 mg for < 3 years and 250 mg ≥ 3 years) to be started at diagnosis and continued until the age of 5 years. Antibiotic prophylaxis can be discontinued at 5 years provided the child has not had a splenectomy or invasive pneumococcal infection and has completed the recommended pneumococcal vaccination series.

- SCD patients should receive routine childhood vaccinations as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization practices (ACIP). The following immunizations are of special importance in SCD:

- Complete the 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine series beginning shortly after birth; in addition, patients should receive the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at age 2 and 5 years.

- In addition to haemophilus influenzae B vaccination, meningococcal vaccination is recommended at ages 2, 4 and 6 months of age and a booster dose at 12-15 months. Further meningococcal boosters to be administered three years after completion of primary vaccination series and every five years thereafter.

- Yearly influenza vaccination is highly recommended.

For catch-up immunization and the most updated immunization schedule refer to the ACIP guidelines at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules.

- Patients should head to the emergency room in case of fever >1010 F for rapid triage, blood cultures and administration of parenteral antibiotics, typically ceftriaxone. Patients less than 1 year of age, or with certain other risk factors such as high fever or high white count, will be admitted for monitoring on antibiotics due to their higher risk of sepsis. Patients with fever will also need to be assessed for acute chest syndrome, which is the development of vaso-occlusion in the lungs and rapid development of lung infiltrates. Pediatricians need to counsel families on the importance of having a working thermometer, measuring fever, and showing up to the emergency room for fever >1010 F even in the presence of focal symptoms of infection.

Vaso-occlusive pain

Sudden onset of severe musculoskeletal pain episodes called vaso-occlusive crises is the hallmark of SCD. Dehydration, hypoxia, cold exposure and mental stress are some of the well-known triggers for the pain crises. Great advice to give patients would be to stay well-hydrated, to avoid swimming for more than 15 minutes at a time and dry off immediately, to dress warm, and to avoid hypoxic conditions such as high altitudes. Once a pain crisis begins, it is important to control the pain in a rapid manner as ongoing pain itself can escalate the crisis further. Most pain can be managed with around-the-clock Ibuprofen and oral opiates at home, but persistent or severe pain requires hospitalization with fluids and aggressive pain management with intravenous opiates. Unfortunately, there is significant stigma associated with SCD patients seeking health care for acute pain. It is important to understand that there are no lab tests or vital signs that are a reliable indicator for pain in SCD and the patient’s complaints of pain must be adequately addressed.

Splenic sequestration

SCD patients have chronic anemia, but the baseline hemoglobin varies widely depending on the genotype and the current therapies they are receiving (Hb SS and SBeta0 thalassemia have more severe anemia than Hb SC and SBeta+ thalassemia). It is important for the patient’s family and pediatrician to be aware of the baseline hemoglobin value so they can detect any acute changes that may occur from complications such as splenic sequestration. Sudden enlargement of the spleen from the trapping of blood in splenic sinusoids results in a >2 g/dl drop in hemoglobin and/or thrombocytopenia. It is typically seen in children less than 5 years old in Hb SS and older children with Hb SC presenting with pallor, lethargy and fussiness, and sometimes with hypovolemic shock. Management includes measured blood transfusions and close monitoring. Parents should be taught to palpate the belly and feel for the spleen of patients from the newborn period. Suspicious symptoms and an enlarged spleen should prompt immediate evaluation for splenic sequestration.

Aplastic crisis

Patients with SCD have increased hemolysis and are dependent on a rapid bone marrow turnover with high reticulocyte count to maintain their baseline hemoglobin. Infections such as parvovirus can temporarily suppress the bone marrow, resulting in a significant drop in reticulocyte count and hemoglobin. These patients mostly present with symptoms of significant anemia, sometimes with fever, and usually need blood transfusion support until spontaneous recovery of their marrow.

Priapism

Priapism is a sustained, unwanted painful erection that occurs in up to 36% of males with SCD, typically starting in adolescence, although it can occur in the younger kids. Brief, self-limited episodes are more common and are mostly managed at home with hydration, pain control and oral sympathomimetics. Major episodes lasting longer than four hours can cause ischemia and damage to the penile tissue, longer durations further increasing risk for erectile dysfunction. Major episodes require urologic intervention and exchange transfusion in difficult cases. It is important to talk to boys with SCD from a young age regarding this sensitive topic so they understand this is a medical issue and remain open in their communication.

Stroke risk in sickle cell disease

Stroke is one of the most devastating complications in SCD, and in the absence of primary stroke prevention it can occur in up to 10% of patients. Yearly screening with transcranial Doppler imaging to measure cerebral blood flow velocities helps identify patients at high risk of stroke. In these high-risk patients, institution of chronic blood transfusion regimen to suppress the HbS has resulted in a decline in stroke incidence, but the risk remains, especially in patients who are not adherent to therapy. Focal limb weakness, dysphasia or aphasia, visual disturbances, facial weakness, and seizures are some of the symptoms that families have to be taught to watch out for and to seek emergency care if they appear. Treatment of acute stroke involves initiation of exchange transfusion and supportive care. Even in the absence of signs of overt stroke, silent infarcts seen as MRI changes are thought to occur in as high as 35% of children with SCD and can cause cognitive decline and poor school performance.

A note on hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is a disease-modifying therapy that should be offered to all patients with Hb SS and S Beta0 thalassemia who are 9 months or older and acts mainly by increasing levels of fetal hemoglobin, among other therapeutic effects. We start the conversation early with parents about hydroxyurea so parents can make an informed decision by 9 months of age. It has well-documented clinical efficacy over the past three decades in decreasing acute pain events and acute chest episodes, among other clinical benefits seen in patients. Long-term observational studies have not shown any excessive myelotoxicity or adverse effects on growth and development, and hydroxyurea is considered standard of care for Hb SS and S Beta0 thalassemia patients.

SCD resources for providers

- Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease, expert panel report 2014

- Health supervision for children with sickle cell disease, American Academy of Pediatrics

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

SCD resource for parents

- California Department of Public Health resource at the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation website

- A Parent's Handbook for Sickle Cell Disease Part I - Birth to Age 6

- A Parent's Handbook for Sickle Cell Disease Part II - Ages 6 - 18