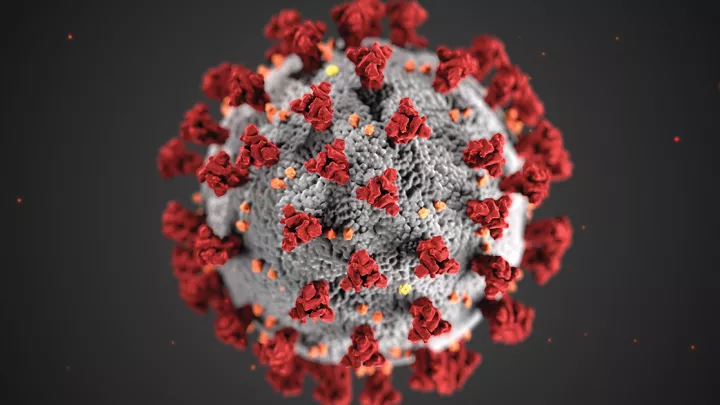

Can COVID-19 Cause Diabetes?

Can the novel coronavirus—SARS-CoV-2—cause diabetes? No one knows, but Senta Georgia, PhD, is trying to find out. Dr. Georgia, an investigator in The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, recently received a $100,000 peer-reviewed grant from the American Diabetes Association to examine the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on pancreatic beta cells (cells in the pancreas that make insulin).

Below, Dr. Georgia discusses her team’s research—and the link she suspects she’ll find between the virus that causes COVID-19 and diabetes.

What do we know so far about SARS-CoV-2 and diabetes?

We have a lot of suggestions, but we don’t know very much. Having diabetes has been associated with worse outcomes from COVID-19. But there have also been reports of adults with COVID-19 developing diabetes. A small study in the U.K. found a doubling of new-onset Type 1 diabetes cases in children since the pandemic began. And at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, we’ve seen an increase in new cases of Type 2 diabetes in children.

So there’s a lot of smoke, but nobody has been able to identify the fire yet. We don’t know if there’s actually a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pancreatic beta cells, or whether the infection itself is eliciting a hyper-inflammatory response that is then mis-programmed to attack beta cells.

What are you studying?

We’ve partnered with a company that is doing preclinical trials for a DNA vaccine for COVID-19. That company is sending us pancreas samples and blood samples that are collected from in vivo models after COVID-19 infection. And then we’re studying those samples to see if there’s a loss of beta cells or a change in beta cell function after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

By using high-powered imaging techniques—different kinds of microscopes—we can see if the beta cells are healthy or sick, or if the amount of insulin they have per cell is normal.

What questions are you looking to answer, and what do you think you’ll find?

One of the questions we’re looking at, using electron microscopy, is whether the virus is actually directly infecting pancreatic beta cells. And if so, does that infection then change the metabolism of the beta cells? Because if you change the metabolism—meaning, the way those cells process energy—then those cells are not going to be able to secrete insulin as effectively.

We hypothesize that SARS-CoV-2 is directly infecting beta cells and thus causing a change in their capacity to secrete insulin—resulting in the loss of beta cell function and the eventual development of diabetes.

Type 1 or Type 2, or either?

Either. We haven’t looked at enough samples yet. They’re caused by very different things and have different markers, and we’re still sorting through that.

What leads you to believe that the virus is directly infecting beta cells?

In vitro studies (cells in a dish) have shown that SARS-CoV-2 can directly enter into beta cells. But we don’t know if the virus can do that inside a living organism. That’s why we’ve moved on to study these preclinical models.

Interestingly, the original SARS virus in 2003 was also linked to the onset of diabetes.

Could COVID-19 lead to diabetes even years after an infection?

Potentially. People have a wide range in the number of insulin cells they have. Studies show that when you get down to 2%—meaning, beta cells make up 2% of your pancreas volume—your blood sugar will creep up. And when you get to 1%, your blood sugar shoots up.

So, if you are in that 3% to 4% range—and if you get COVID-19 and lose half your beta cells—you might develop diabetes immediately. But say you have 8% beta cell volume and get COVID, and you lose half your beta cells. That brings you to 4%. You’re going to think you’re completely fine. But as you age and have stressors to your metabolism and lose more beta cells, that’s when those people could get diabetes. And if it hadn’t been for COVID-19, they probably never would have developed diabetes at all. So that’s a huge concern.

Again, we don’t know if a direct link is happening. That’s what we’re trying to find out.

What’s your hope for your research?

We want to understand why we are seeing this increase in patients with new-onset diabetes, in both adults and children. We also want to know why patients who already have diabetes who get COVID-19 need more intensive glucose management and insulin therapy.

But most importantly, we need to understand the molecular mechanisms that may be driving these phenomena. If we can understand how it’s happening, we can then seek to develop therapies to prevent it, or at least to mitigate it. That’s ultimately what we’re hoping to do.