Worth the Wait: A Year of ‘Will’ Power

On a picture-perfect summer day at the lake in August 2016, William Lievense, then 9, stood at the edge of the dock, ready to jump gleefully into the water one more time.

At that moment, his life was still the normal life he had always known. In that life, he was the fastest kid on the soccer field, ran the most laps at his school’s jog-a-thon, and went on endless adventures with his big brother, James, and his best friend, “Big Will,” both in the online game of Minecraft and in the real-life world of his backyard.

But when William’s body plunged into the water that day, that normal life vanished. Suddenly, he didn’t feel right. A minute later, he climbed out of the lake, made a strange sound—and passed out cold on the dock.

A shocking day

Although William woke up quickly and seemed OK, his mom, Stephenie Lievense, felt a worry begin to gnaw at her: Could William have a problem with his heart?

The idea wasn’t far-fetched. Stephenie has a heart condition called arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), a genetic condition that causes the muscle in the heart’s right ventricle to slowly be replaced with fatty, fibrous tissue. ARVD can cause arrhythmias—abnormal heart rhythms—that can cause sudden death.

Stephenie’s ARVD is relatively mild, but William had a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. The condition typically doesn’t show symptoms in childhood, but when the family returned home to Altadena from their vacation, they took William to a cardiologist affiliated with CHLA.

The news was not good. He had telltale signs of ARVD, and his right ventricle was twice the normal size. The incident at the lake had likely been an arrhythmia. Will's cadiologist cautioned that he would need to stop all sports and running immediately.

“That was a completely shocking day,” his mom says. “But we had no idea how much harder it was going to get.”

No alternative

Less than a week later, William passed out on the playground at school.

His parents rushed him to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where doctors put him on anti-arrhythmia medication and implanted a defibrillator in his chest—a pacemaker-like device that could shock his heart into normal rhythm if needed.

But a month later, while on a planned trip to Cambria, William’s heart went into a life-threatening, inconvertible arrhythmia—one so severe that even his new defibrillator couldn’t correct it without help. Fortunately, during the ambulance ride to the nearest hospital, with the assistance of his defibrillator and two intravenous medications, his heart returned to a normal rhythm. A few hours later, Stephenie and William were strapped into a helicopter, charging down the California coast.

At midnight on Oct. 18, 2016, they landed on the rooftop of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. A few days later, doctors broke the news: William’s condition was so severe that he had no alternative but a heart transplant.

William would also have to move into the hospital and undergo continuous monitoring of his heart. Although he felt OK, his risk of death from a sudden arrhythmia was high. He had to be hooked up 24/7 to IV medication; he couldn’t even leave the hospital floor. And it might be a long time before he could get a new heart, as there are few donor hearts available for children his age.

Stephenie and Dan Lievense, William’s dad, were stunned. Just two months ago, their son had been getting ready for soccer season. How could their lives have changed so fast?

“At first, we were just trying to survive,” Stephenie says. “Then we settled in for the long haul.”

Minecraft and mischief

They fell into a routine. William had an hour of school each day, plus music and art therapy and physical and occupational therapy weekly. Every day, he read his favorite Rick Riordan books, did homework, watched movies, and played Minecraft with James and Big Will via a FaceTime connection.

The family tried to keep life in a hospital room as interesting as possible. Stephenie ordered science experiment kits online, and she and William dissected a frog and a cow eyeball. The pair became notorious for playing practical jokes on the nurses, which included the science experiments (don't ask).

The nurses and staff on the Cardiovascular Acute Unit became their family—people like Penda, charge nurse Ani, and nurses Bri (whom he nicknamed “Fancy Cheese”) and Kat, who became “Kitty Kat.”

Jondavid Menteer, MD, medical director of the Heart Transplant Program at CHLA, gave William a remote-controlled Minion as a gift. Every day, William took the Minion on his walk down the hallway.

“It was those extra little things that the people at CHLA do,” Stephenie says. “They’re just awesome. You can tell they’re not just doing a job. They really take care of people.”

Still, the months dragged on. William’s heart needed continual medicine just to keep pumping. There was a reason he only took one short walk a day: His heart couldn’t handle any more.

“On the outside he looked pretty good,” Menteer says, “but his heart was getting worse on a daily basis.”

‘Every day was good’

In the early-morning hours of Sept. 3, 2017, William received his new heart. Two weeks later—after 336 days at CHLA—he finally went home.

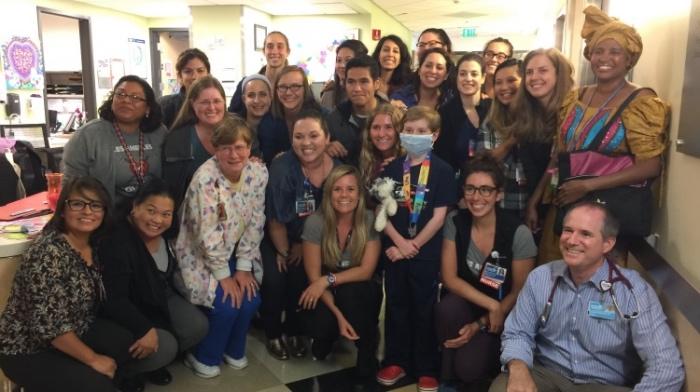

It was a day of celebration. Nurses, doctors and staff cheered as William took one final victory walk down the hallway. Everyone posed for one last photo. Outside, firefighters from the Los Angeles City Fire Department, where Dan is a fire captain, were on hand to send them off.

Today, it’s been nearly six months since William’s transplant. Now 11, he’s back riding his bike and walking his dog. In April, he’ll return to school with his fifth-grade class.

“I’m doing awesome,” he says cheerily, talking a mile a minute. “Now I’m able to run around outside. We got two new kittens when I got out of the hospital. And me and my brother and my best friend like to do Nerf gun wars,” he continues excitedly, describing a fort they’ve created out of a shrub in the backyard. “It’s really fun.”

With perfect 11-year-old honesty, he says life in the hospital was “pretty boring.” But he has some people to thank. “I want to thank the doctors, who were really sweet and nice, and the nurses—they were really cool and chill—and my teacher, Miss Aloi,” he says. “And I want to thank the donor for my new heart.”

His mom says her own happiness is always mixed with thoughts of the donor family and the generous decision they made that saved William’s life.

“We are so grateful to that family. I think about them all the time,” she says.

She realizes now that their long wait at CHLA was a good thing. “Every day that we waited,” she adds, “was another day that family got to have with their child.”

The long wait gave her something else, too: a new way of looking at life.

“It really forced me to live in the moment-by-momentness of life and to appreciate what each day had for us,” she explains. “And you know what? Every day was good.”

How you can help

To help kids just like William, consider making a donation to Children's Hospital Los Angeles. Visit CHLA.org/Donate.