A Father in Full

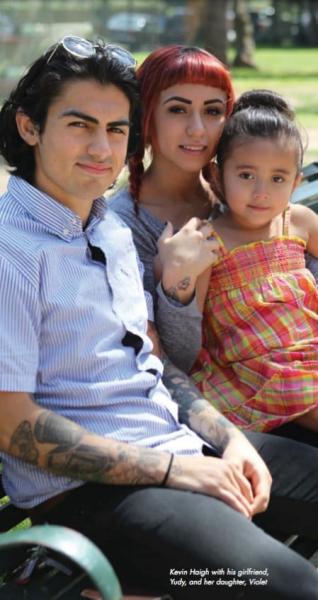

Kevin Haigh admits to being a father-in-progress. “I don’t know what I’m doing, actually,” he says.

But he’s trying, having spent the past 18 months attending L.A. Fathers, a support program for young Los Angeles-area fathers run by the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine. And he’s made strides, judging by his small smile as he relates how his girlfriend’s 3-year-old daughter greets him when he comes home.

“She goes, ‘Hey, Kevin!’ and I go, ‘Hey, Violet,’ and I tap her on the head. Then she asks me for food. I can’t really make anything, so there’s Lunchables in the fridge.” Here’s where he shows his maturing parenting skills. “I know that’s bad—a little fattening.”

The perils of processed food may not be one of the lessons Haigh picked up at L.A. Fathers, but his general attention to fatherly responsibility can certainly be traced back there. He is an exemplary case, having advanced from participating in the program to being employed by it, but he’s not an unusual one. Hundreds of young men who want to do right by their children, whether they’re fathers by birth or by circumstance, as in Haigh’s case, have joined L.A. Fathers since its introduction in summer 2012.

Becoming a program in full

Funded by a grant from the U.S. Office of Family Assistance (OFA), L.A. Fathers is an outgrowth of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine’s Project NATEEN, which provides services for teen moms. The program loads a trio of workshops on parenting, healthy relationships and job development into weekly two-hour sessions. It’s that last item—job development—that generally hooks recruits. “Basically, there are a lot of guys out there who need work, and that’s our angle—helping them get jobs,” says Frank Blaney, program coordinator.

There was a time when Blaney himself would have been a candidate for the program. He grew up poor, the son of a single mother; his dad left when he was 5. At age 24, with nothing but a high school diploma to lean on, he became a father. “I think that background influenced my decision to get into this type of work,” he says.

Now 51, Blaney holds a master’s degree in negotiation, conflict resolution and peace building and facilitates the healthy relationships component of the program. Each session establishes a new dialogue. He gives the example of a recent class that focused on self-care. “We asked them, ‘What do you guys do when you get stressed?’” A tai chi enthusiast and teacher, he demonstrated an option perhaps they had never considered: deep breaths.

Blaney came to L.A. Fathers in April 2012, a precarious time for the program as it struggled to attract interest. The first workshops drew barely half a dozen attendees; the tally for the year reached only 30, far short of the annual goal of 250 participants spelled out in the funding proposal. OFA officials weren’t impressed.

“They were expecting that 250,” Blaney says. When they didn’t get it, they flew in to find out why. “They weren’t real happy. We were all trying hard, but they were like, ‘What’s going on?’”

The on-site visit prompted a change in strategy. Program leaders abandoned their reliance on referrals from community and governmental organizations. Instead, they got personal. Blaney and two other case managers rode around on scooters to parks and housing projects, and even at opening day at Dodger Stadium, approaching young men who looked the part—namely, they were with a kid or were pushing a stroller. “We’d ask, ‘Hey, are any of you guys dads?’ Blaney says. “It’s not necessarily the safest way, but we got some guys signed up, and we just kept with it.”

The new ground game, complemented by a marketing campaign that placed posters promoting the program in the city’s trains and buses, found the mark. Recruiting numbers surged in the spring. Five sign-ups in February and 18 in March shot up to 62 in April and 74 in May. Enrollment totaled 310 by year’s end, safely clearing the target. The Wednesday workshop grew so large that a Tuesday class was created to accommodate the overflow. “We’re getting our guys,” Blaney says.

Haigh, 23, was convinced to enroll by two friends already in the program, who told him he needed tips on parenting his girlfriend’s daughter. But he already had an interest in social services, having taken two sociology classes at Los Angeles City College. Plus, he had his own personal history driving him. His father left when Haigh was little, chasing a drug and alcohol addiction. Haigh says he was determined to “deviate from his course. I knew I had to make a change.” He now works for the program, reaching out to potential participants on the Metro train to and from his home.

He still takes part in the workshops, speaking up whenever he thinks the other fathers are hesitant. “One of the facilitators might say: ‘How would you talk to your child, in what kind of tone? Would you get down on your knees to their eye level so they don’t feel scared?’ If dads aren’t comfortable saying it, I’m thinking that they might be thinking it. I usually put in my 2 cents.”

For any and all parents

The program is aimed at young men ages 15 to 25, but as a recipient of federal funding it can’t turn anyone away, which leaves its doors open to some nontraditional fathers—such as mothers. The only genuine requirement is nerve, which is what got Emely Zavala in.

As a high school graduate past the age of 18, Zavala, a 22-year-old single parent of an autistic child, didn’t qualify for programs designed for young mothers, including the one run by Project NATEEN. She saw the L.A. Fathers poster on the Metro and called up. The voice mail response said to leave a message if, among other options, “you’re acting the role of a father.” She was—and so she did.

“I’m a risk-taker,” says Zavala. “I’ve always put myself in awkward situations.”

This one was no different initially, as she was met with some immediate curiosity from the men in the program. “One of them asked me why I was there. He said, ‘Aren’t there other programs for you?’ I said, ‘Maybe there are, but I like it here. I feel comfortable talking to you guys.’”

Zavala is now in the midst of her second session, with no intention of leaving. “I’ve given up in so many other therapies, but this is the first group that I’ve not given up on. I feel like I need to go, like I’m free. Even if the day has been super-negative, it becomes positive as soon as you walk through that door.”

The novelty of her presence wore off months ago. “They’ve accepted me. I’m like one of the guys.”

Not entirely. Though the program isn’t obliged to make any modifications for her, one accommodation was provided—a slight edit to her diploma for completing the workshop. “They all say, ‘for being a committed father’ at the end. Mine says, ‘for being a committed mother.’”

As seen in Imagine Spring 2014.