Can a Tiny Fish Transform Treatment for Childhood Cancers?

A physician-scientist is harnessing the power of zebrafish—and a new, state-of-the-art facility—to develop innovative treatments for solid tumors in children.

You might think you couldn’t possibly have much in common with a fish—especially an inch-long member of the minnow family with colorful, zebra-like stripes. But James Amatruda, MD, PhD, begs to differ.

“Zebrafish are, in many ways, quite similar to humans in anatomy, physiology and disease susceptibility,” says Dr. Amatruda, Head of Basic and Translational Research for the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “They’re vertebrates, we share 70% of the same genes, and 80% of disease-causing genes in humans have a corresponding gene in zebrafish.”

These traits make zebrafish an excellent model for studying human disease. To harness this potential, Dr. Amatruda is leading the new Alfred E. Mann Family Foundation Zebrafish Laboratory at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The 3,000-square foot lab will support scientists studying many pediatric conditions and house up to 120,000 zebrafish.

“We have big ambitions,” he says. “We want to study all the cancer genes. We want to study thousands of drug treatments. And we want to do it all very quickly, on a large scale.”

DEVELOPMENT GONE AWRY?

Dr. Amatruda, who holds the Dr. Kenneth O. Williams Chair in Cancer Research, studies solid tumor cancers in children, including liver and kidney cancers and sarcomas (cancers of the bone, muscle and connective tissue). Although treatments like surgery, chemotherapy and radiation have dramatically improved survival rates for these cancers, they often come with toxic and long-term health effects. And not all patients respond to them.

“We’re starting to hit a plateau,” he says, slapping one face-down palm over another, mimicking a ceiling. “We need new approaches.”

One focus for his team: the link between these cancers and early development. Normally, a child’s primitive fetal cells grow and mature into organs, bones and muscles. Once this tissue is fully formed, the cells stop dividing. But in children with solid tumor cancers, the cells keep growing long after they’re supposed to stop.

“Most adult cancers are due to aging and environmental effects,” Dr. Amatruda notes. “In children, it’s a different story. We think that it’s during these key moments in development that the tumor process starts.”

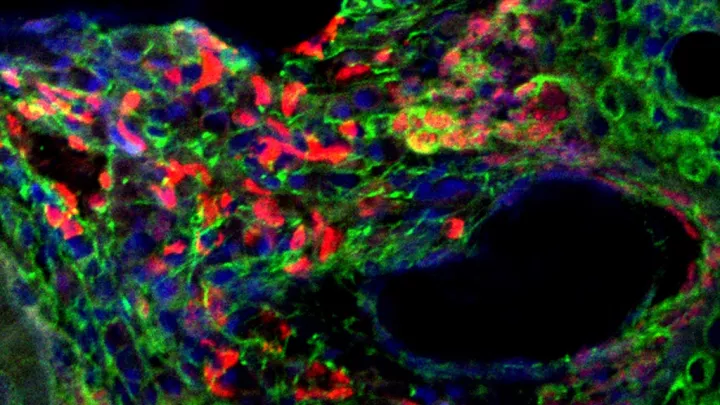

To understand this process at a deep biological level, researchers need a living model. That’s where those tiny zebrafish come in. The fish grow quickly and are initially transparent—making it easy to observe both normal and tumor development.

NOVEL APPROACHES

Dr. Amatruda’s team has developed a zebrafish model of rhabdomyosarcoma, a muscle cancer in children. The team found that a cancer-causing “fusion oncogene" called PAX3-FOXO1 disrupts muscle development in children, causing these cells to keep growing instead of maturing.

The team is now validating possible pathways for blocking this disruption. The approach would be highly targeted to tumor tissue—and potentially less toxic to normal cells. “It’s always the dream to target the tumor and none of the normal tissue,” he says. “It’s imperfect, but there are some tantalizing hints that there’s a real therapeutic avenue forward.”

In Ewing sarcoma, a bone cancer in kids and young adults, the fusion oncogene involved is so toxic, it’s impossible to study in other preclinical models. But Dr. Amatruda’s team created a model in zebrafish.

Over just a few weeks, researchers can track a tumor’s development, gaining insight into how normal cells in the tumor’s “neighborhood” are coerced into promoting the tumor’s growth.

“We’re looking at the most specific way to target this interaction,” he says. “With our zebrafish model and this beautiful new facility, these studies are now accessible to us.”

As a physician-scientist, Dr. Amatruda is passionate about developing these new approaches for young patients—including his own.

“I never feel like progress is fast enough, because there are kids right now struggling with these cancers,” he says. “Working with patients and families is a tremendous motivator. It’s a continual reminder of what’s at stake.”