Why do some neuroblastoma patients have “dancing eyes”?

Researchers at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, led by principal investigator and acting division head of Neurology Wendy Mitchell, MD, have been at the forefront of studying treatment and outcome Opsoclonus-Myoclonus Syndrome or OMS (also known as the “dancing eyes” syndrome or Opsoclonus-Ataxia).

OMS affects roughly 1 in every 200 patients with neuroblastoma, a cancer of the sympathetic nervous system. Neuroblastoma is found in approximately 80% of infants and toddlers with OMS. It can also occur in older children and adolescents, rarely related to neuroblastoma or other cancers, more often after infection.

While neuroblastoma in patients presenting with OMS has nearly a 100% event-free survival rate, OMS can have severe short- and long-term neurological and developmental effects. It is thought that OMS is triggered by immune responses to the neuroblastoma, with immune cross-reactivity with normal cells in the brain, most likely in cerebellum. While the tumors themselves often regress or even disappear as a result of immune response, the same immune responses can also adversely affect the brain, resulting in cognitive, adaptive, behavioral, and motor deficits. These immunologically based responses continue, despite removal of the tumor, resulting in ongoing symptoms of OMS.

Patients with OMS often have unsteadiness of walking, or lose ability to walk (ataxia), tremor of hands, as well as rapid, “dancing” movement of the eyes in horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions (known as opsoclonus). Patients may experience nausea and severe behavioral deficits, including profound irritability. Even after treatment with strong immunosuppressive medications, children with OMS may have recurrent symptoms with minor infections, or when their immunosuppressive medications are lowered. They may also often experience long-term cognitive and motor difficulty, such as speech and language deficits, as well as difficulty sleeping. The goal of OMS treatment is to reduce or eliminate these long-term conditions.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Child Neurology, Mitchell and her team reported that aggressive immunosuppressive treatment is key to improving long-term behavioral, cognitive, adaptive, and motor functions to normal or near normal levels. Treatment of OMS generally combines multiple forms of immunosuppression, including a medication that targets B lymphocytes, a type of immune cell. In OMS patients, activated B lymphocytes been found in increased numbers in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Immunosuppressive medications used to treat OMS include corticosteroids and/or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which often help dramatically and immediately. However, side effects are severe and treatment cannot be sustained with ACTH or corticosteroids alone at high doses. Intravenous immunoglobulin is also used to suppress inflammation along with chemotherapy agents which also reduce the immune response. More recently, the drug rituximab has been added to standard OMS treatment to decrease the number of activated B cells in the cerebrospinal fluid, promote longer term remission, and reduce the need for very long term high dose corticosteroids or ACTH.

Many questions about OMS still remain unanswered. It is unclear whether a specific tumor antigen in the neuroblastoma is associated with the development of OMS, or exactly what the immune target is in the brain. Mitchell also suggests there may be a second immune stimulating event in addition to the neuroblastoma (such as an immunization or immunization) that triggers OMS.

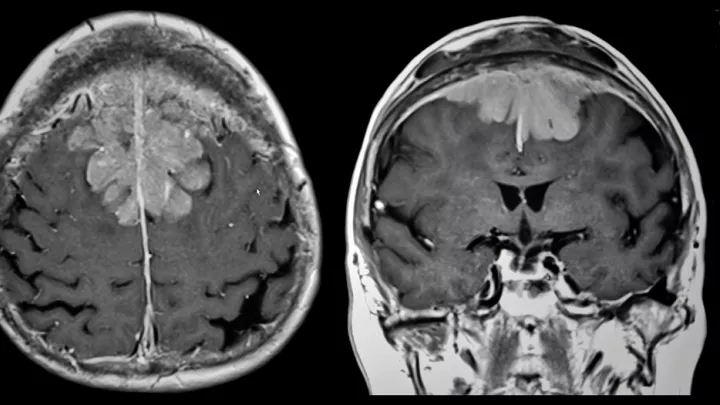

“The important takeaway message for parents is that OMS can be difficult to diagnosis,” said Mitchell. It is also difficult to find the neuroblastomas, which are small and hidden. “It is especially critical to include the expertise of a radiologist who is highly experienced in cases of OMS, and in detecting occult neuroblastoma tumors.” Mitchell and the team of radiologists at CHLA, who frequent provide second opinions in OMS cases, and have detected tiny tumors missed at other pediatric centers. CHLA surgeons have considerable experience in removing the small neuroblastomas that are found.

![10E4_CHLA90_2[2] (tumor-associated macrophages)](/sites/default/files/styles/16x9_half/public/thumbnails/image/10E4_CHLA90_2%5B2%5D%20%281%29.jpg.webp?itok=mArbKB0V)